On the way to and from our 2023 residency in Finland, we drove through Poland and the Baltic countries. Almost everywhere the tension of the neighbouring war could be felt. The roads to Ukraine were rutted by heavy traffic of trucks and armoured vehicles, and sometimes we ran into military convoys. Often we were within just a few hundred kilometres from the Russian border – as was the location of our residency, Posio.

The tense feeling of a war going on nearby intensified the shock we felt on our return journey, at the discovery of a museum that was both fascinating and incredibly morbid: The Corner House in Riga, Latvia.

We found it more or less by accident, and at first we were not allowed to enter. It was June 14, the day the Latvians and other Baltic countries commemorate the thousands of citizens deported to Siberia by the Soviet occupiers almost 80 years ago. There was a television crew in and around the building, making a memorial program.

In the afternoon, some visitors, including us, were allowed in and given a tour.

The Corner House is a Jugendstil edifice, built to house shops, offices and apartments – like many of the elegant monuments you can find in the pretty center of Riga. But during the Russian Occupation (1940-’41 and from 1944 to 1991) the pretty building served as the headquarters of the KGB. Between 1941 and 1944 it was used by different Nazi groups.

After the restoration of Latvia’s independence in 1991, the Corner House was turned into a Museum of the Occupation of Latvia. The extraordinary thing is that nothing in the building was changed since the moment the KGB left – or at least very little. And the tour, directed by a former prisoner, told us a grim story about years of oppression, torture and executions.

We had joined the tour innocently, my curiosity being more or less focused on the historical and artistical value of the building. From the year we had participated in the 2016 Kohila Art Symposium in Estonia, I had become intrigued by the – impressive, but rather arrogant – Prussian architecture that dominated the Baltic before the revolutions of the early 1900’s. The monumental Estonian music school in which we were housed in 2016, had been Arvo Pärt’s alma mater.

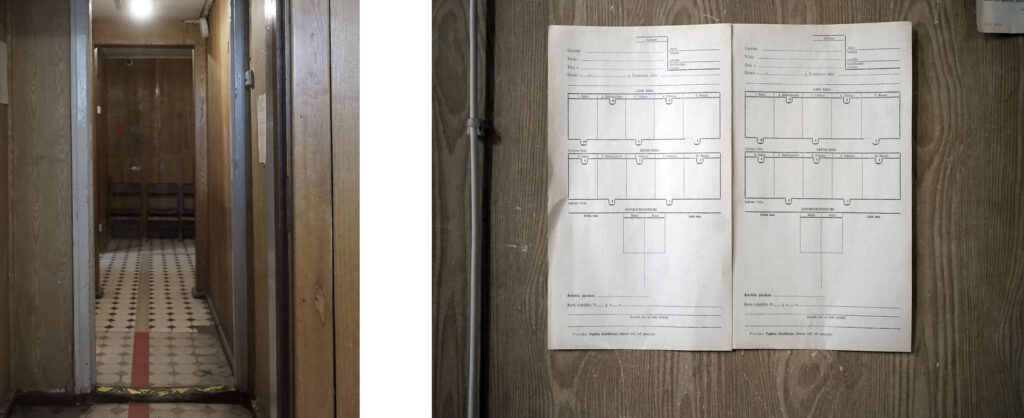

From the outside, the Corner House fits its classification as art nouveau monument. Inside, however, it looks like a meticulously built model of hell.

Every room, every piece of furniture has been used to humiliate and degrade human beings. Every surface, every object is broken, soiled, smudged by the overpopulation of terrorized prisoners.

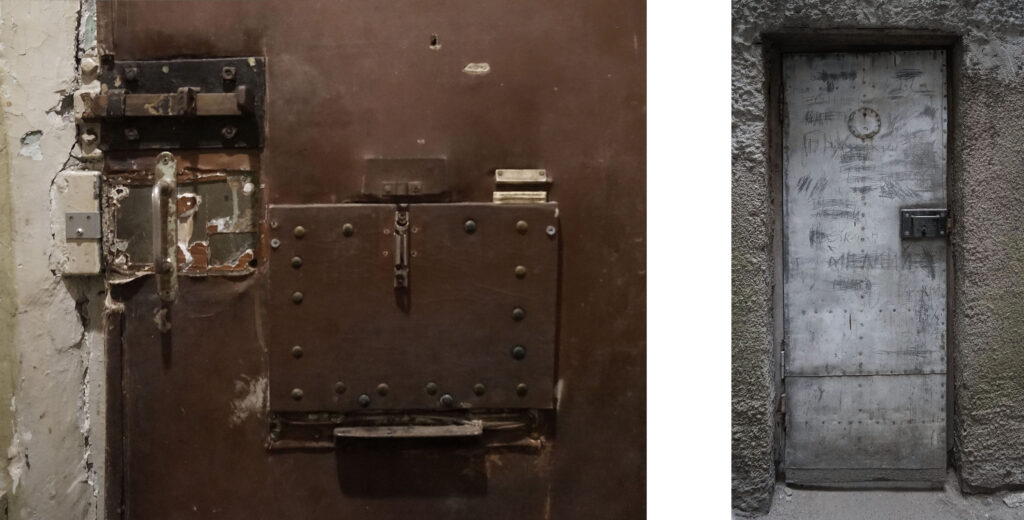

It is clear that the only function of the doors in the building was to keep them locked in – they are dented by decades of successive bolts and latches. Unavoidable repairs were made using only the cheapest materials and scrap iron. Everything is dirty, cracked and literally worn to the bone.

/

Even the graffiti was obliterated to prevent communication between the inmates. I did not know how to react to this hateful, terror-stricken environment. The tour leader related the history of the place, recounting anecdotes from his own experience. He made desperate jokes. He tried to involve the group of tourists by locking them up in a cell for a few minutes.

But they had to do without me, I know what it is like to be locked up. I had to look at the others through the one-way mirror in the adjoining room.

I felt terrified and completely alienated and the only thing I could do was take more and more photographs.

But I am not interested at all in becoming the author of pictures of hell. I always feel that I am not a photographer – Yes, of course, as an artist I use images. But mostly, I use images to get them out of my way, out of my mind.

[Images – I find them everywhere: on the internet, in my camera, in books and papers and yes: on the street, I don’t care.

Once, I accidentally found a strip of negatives taken in Surinam, lying on the street in front of my studio. Within hours they were converted into central elements of the installation on South-America I was working on.]

When I review the pictures I took in The Corner House, the surface of the floors, walls and ceilings seem to me fundamental. They are like the scans of volcanic fields I pictured in Iceland, using a drone, like the memories of country paths in Afghanistan, worn-down walls in India.

Pictures that turn out incredibly detailed and hugely interesting, even threatening, but so remote and unearthly that it is impossible to establish a relation with them.

To show that world, we have to change the nature of the image itself: no longer to represent a hole in the wall, a window to look out of – but to construct a cage, a diving bell, a uniform.

What else can you do with these pictures? Images encircling cruelty, betrayal, boredom, guilt, poverty and indifference. Images of walls with the impact of execution bullits.

And perhaps the most depressing picture of all: the photograph of the postbox installed at the entrance of the KGB office, in a place where nobody could be observed.

An anonymous brown box, with a narrow slit to insert letters informing on your fellow men, neighbours, family…