From Launceston to Bilpin

Marielle van den Bergh, March 2020

Tasmania

In 2006 we went to Tasmania for the Poimena residency at the Launceston Grammar School in the second city of Tasmania: Launceston. The artist and head of the Art Department, Katy Woodroffe, had initiated the residency. We, Mels, our 8 year old son Quirijn and I, slept in a small unit, which was built to accommodate visiting parents of the boarding school students. We had our meals in a Harry Potter-like hall and had a studio in the annex to a Victorian villa, where the Art School was situated. In order to be able to make my installation of paper, I had written in the proposal, that we would travel through Tasmania to find a characteristic feature of the island, as a starting point for my work.

I also had to gather fibres, which would be a constructive element in producing the paper works.

Katy has a magic wand – she waved it and we were provided with a car. We travelled for a week through Tasmania and fell completely and for ever in love with the island and it’s pristine, unspoiled nature. Especially the giant Old Growth eucalyptus trees (dating from pre-colonial times) are magnificent. Maybe I should say: were magnificent. We found out that these hundreds of years old trees were being harvested at the time (maybe still are?) for the Japanese cardboard industry. Lots of bumper stickers on cars protested against the destruction of these irreplaceable natural resources and symbols of beauty.

For a Dutch girl, with half her native country below sea level, and a natural instinct that is aware of the surrounding water at all times, the sight of the black, charred landscape was quite impressive. But nature was able to regenerate itself, we could see that from the fresh green sprouts on trees and on the ground. However, the carbonised wood, intensely black and spread as far as the eye can see, made us realize what kind of inferno had caused it. My installation at the end of the two months was called Burned Bush and was presented in the Poimena Gallery during our show ‘Double Dutch’. I used Chinese rice paper on a frame of local fibres (tree bark and button grass). I had worked before with these kinds of materials and built quite large installations with it in the past.

The wild primal nature of Tasmania enchanted us, especially in places like Cradle Mountain with its multitude of lichens and ferns, and we marvelled at the mountain ridge of the Walls of Jericho and the orange lichen on the shore boulders in Bay of Fires.

Tasmania revisited

After 2006, we revisited Tasmania in 2018, and found some things had changed over those years. Tasmania has become a popular tourist destiny and is now quite fashionable. Yuppies from all over the world can be spotted in the island’s main city Hobart. Traffic is denser; it is hard to stop on the two-lane roads. More “foreigners” (mainland Aussies) have settled in Tasmania. Katy used to joke that Tassie was usually left off the map of Australia. In 2018 it was definitely a focus point of many people and companies with dubious agenda’s. There is a plan to built a luxury resort in the middle of a nature reserve – the rich will be flown in by helicopter. Somehow it also felt as if a lot of the Old Growth trees were gone. And there was snow at Cradle Mountain, which meant that the accommodation was fully booked and the park was filled with tourists, enjoying the cold winter weather. A bit like a Swiss ski resort in full swing. It looks like Tasmania is being discovered by mass tourism, mostly from east Asia.

The locals are not complaining about these developments – not yet, but many are worried. The best example of a pristine island, featuring breathtaking scenery but with a limited infrastructure – basically a single ring road – is Iceland. In summer, a brief season, the roads are packed with tourists, all driving in the same direction and all meeting each other over and over again during a couple of weeks. There is a discussion among the locals: making money in the tourist industry or voting for a limited access of visitors to the island. During at least part of the year, peace and tranquility are gone.

Back to Tasmania: how to manage large quantities of nature-loving tourists wandering over the wooden floorboards constructed in this beautiful natural reserve? Families of notoriously shy wombats sitting under a small bush may see a thousand people or more passing by on an average day.

BigCi residency in the Blue Mountains

But before visiting Tasmania in 2018 we had been in Australia, at the BigCi residency on the border of Wollemi National Park in the Blue Mountains. BigCi stands for Bilpin Ground for Creative Initiatives and has been founded by director and sculptor Rae Bolotin and her husband Yuri Bolotin, who is an explorer, bushwalker, writer and environmental activist.

Guided by our taste for wild, unspoiled and unusual places in the world, I found the BigCi residency on the Transartists website. Looking at the BigCi website, I found images of the Garden of Stones: an unique region in the Wollemi National Park, where – over thousands and thousands of years – soft sandstone layers were washed away and harder parts, sometimes very thin, curled up into natural sculptures of flowers and exotic plants, all in stone.

The area has also rock pagoda’s, sculpted layered mountains, towering over trees and undergrowth that hide cliffs that are hundreds of meters deep. We had to go there and experience these natural wonders.

We applied as three artists, were selected and went as a family. Our son Quirijn is studying Sonology, Electronic Music at The Hague Royal Conservatoire and wrote his own work plan. My plan was to research the primal nature and use this for the installation I was planning to make for the solo exhibition at Museum Rijswijk, later in the year. The installation would be made from textiles and ceramics and I was granted fundings by the Mondriaan Foundation and Foundation Stokroos. These awards made a big difference, because in Australia you realize that scale is an important requirement in artwork, based on this environment. The art work had to be big and as overpowering as I could make it.

BigCi consists of two buildings, located at the border of

the Wollemi National Park: you only have to cross the dirt road. The main

building is called the Art Shed and is a sober, but extensive multifunctional

two-story building. At the ground level there is the communal studio space, and

at one side the kitchen, bathrooms and Rae’s office. At the back of the

building there is the library and multimedia room. The second level houses the

rooms for more residents. The Art Shed has a very big roof, where rainwater is collected

and directed to two big water storage tanks. The roof is also fitted out with solar

panels, to generate electric power. In an area like this, one has to be

independent and make optimal use of natural resources.

We were, however, located in another building: the Barn, this being a cosy

wooden cabin, with a kitchen, bathroom, a big space where we all could work and

two bedrooms upstairs. This building, which provides a lot of privacy, is often

used by composers.

Rae and Yuri live down the road. On their land is a small

lake, lots of trees, rocks, an abandoned sauna built by early Finnish lumberjacks,

and some of Rae’s breathtaking sculptures.

Rae selects the participants for each month long residency quite precisely,

fine tuning the mix of artists to make an interesting group, with the right

creative chemistry.

Besides the three of us, we were in BigCi with the Australian artist Glenda

Kent, the painter Terri McFarland (USA) and the Chinese, Germany-based artist

Yiy Zhang. Yiy had won an award and was on an exchange programme with the Red

Gallery from Beijing.

The artists-in-residence

Australian artist Glenda Kent usually works with glass, building installations and figures from glass shards. She won the Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize with a cute Teddybear, its ears are shards sticking out of its head. At BigCi Glenda focussed on a rather disturbing natural phenomenon: some trees in the bush are damaged by a beetle, the emerald ash borer, which eats the wood just under the bark. It leaves beautiful patterns on the skin of the tree. Glenda took rubbings and made moulds of an engraved wooden trunk. She also dyed paper with natural colours and used sun light to work on it.

The mould was to be used for glass works later at home.

http://australianphotographcollector.blogspot.com/2017/05/glenda-kent-glass-artist-at-work.html

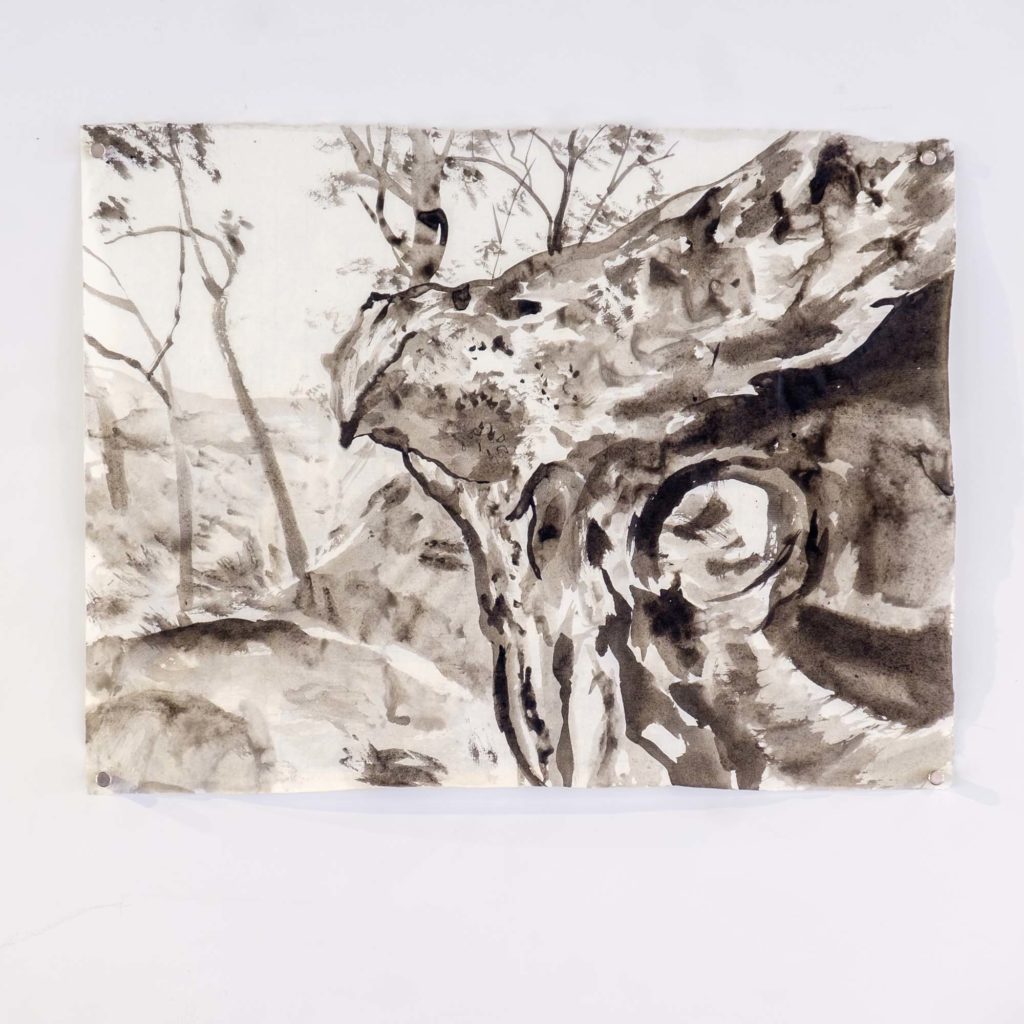

Terri McFarland is a landscape painter, with

a background as a garden designer in California, USA.

She had been on a residency in a breathtaking spot in Norway, making small

paintings of the sea with scattered islands in special sunlight. One day during

the residency, Terri, Mels and I drove out for some time to a valley featuring

huge cliffs. Mels roamed around, taking pictures and taking risks, of which I

was oblivious, since Terri and I were sitting still, making watercolours of the

scenery. We were looking at a rock wall of a few hundred meters height at the

opposite side of the valley, with trees of maybe forty or fifty meters high.

The sun was setting, deepening the colours in the shadows. Besides the shadows lengthening,

time didn’t exist. We could be sitting in eternity. The scale of the

surrounding landscape was frightening and the realisation of the kind of power,

that shaped these volumes, even more so. http://terrimcfarland.com/

Chinese Yiy Zhang is know for her performances, such as “Lebenslinien/ Sisyphos” (Lifelines/ Sisyphos). She specialises in laborious, nearly invisibly subtle interventions in an urban environment, which she then records. At BigCi she prepared a performance, which she enacted during the presentation at the end of the residency, the Open Day. She sewed a coat, shoes and hat with the leaves of the grass tree attached to them. A grass tree is a another of Australia’s weird plant species: it grows 0,8 to 6 cm per year and can reach an age of 350 or even 450 years. In the performance, called “The Shell”, Yiy sat at a cosy table, drinking tea and reading the paper, while wearing the special grass coat and hat. You can find the film on her website: https://www.zhangyiy.com/

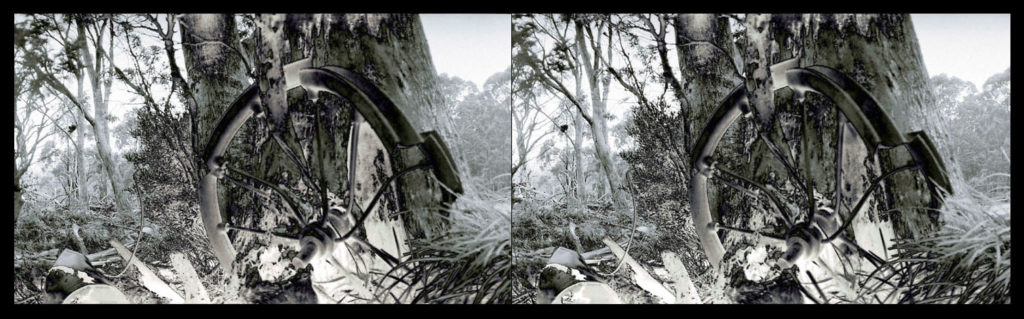

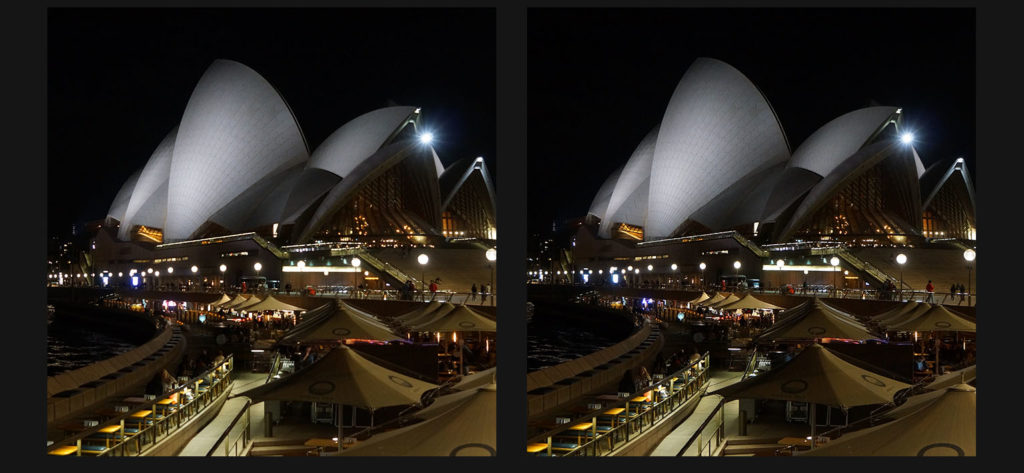

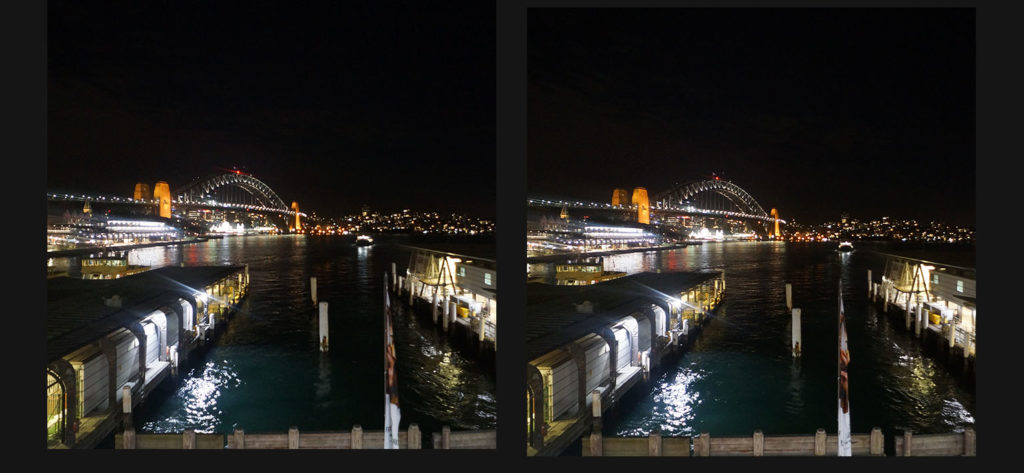

Partner in life, crime and art Mels Dees has written below what his work at BigCi was about. He worked with stereo-photography and computer generated images, based on his photography. While giving his presentation in the library at the Open Day, he told stories about how remains of culture often trigger his mind and creativity. He was very interested in the abandoned town of Newness, an old oil shale mining town in Wolgan Valley, that had been deserted a few decades ago. As a contrast, he used images of the thriving mining town of Lithgow where people are said to be so sure of the everlasting power of coal, that their street lights are never turned off. One of his pictures featured a meteor falling on the main street. The work was immediately purchased by a lawyer who had been fighting the establishment of new mines in the neighbourhood, probably to hang in her office.

Apart from being our son, Quirijn Dees is also a young Sonology student, studying Sound and Abstract Electronic Music in The Hague. He was quite amazed to hear the Australian birds making their natural sounds. If you haven’t heard them in real life, it’s hard to imagine their otherworldly songs. Some birds sound like water running down a plumbing pipe, others make noises like a cockroach with a bad cold. Quirijn had brought his recording device and spent the next weeks running out of the house, microphone in the air and becoming very frustrated because the annoying birds would shut up as soon as he showed his face. However, he managed to get the sounds he wanted, and presented an audiovisual animation at the Open Day, where Quirijn also explained to the public how he proceeded in the production of this work. He called his work: “heavily manipulated and transformed environmental recordings, combined with visual textures captured in the gorgeous environment. Thus creating an audiovisual work inspired by environmental elements.”

Working down under – a residency at BigCi

Mels Dees, 22-02-2019

Australia had already been discovered centuries ago by ‘us’, the Dutch – and some 50,000 years before that by the Aboriginals. But until last year it was the mysterious Southland to me, the place where people walk around with their feet backwards, where trees grow with their roots into the sky, where mammals lay eggs and saltwater crocodiles lunch on tanned bathing beauties.

Twelve years before, in 2006, we had done an amazing residency in Launceston, Tasmania. Nominally Tasmania is of course part of Australia, but the island is far more cosy, friendly and relaxed than the wild and rough mainland. We really felt at home there – it was like an slightly weird, exotic version of our native country – and actually, twelve years ago, we all but stayed there to settle down forever and ever. We’re still not quite sure if it was the right decision to return to Holland…

Mainland Australia is a different piece of cake. Not only does it take the greater part of a day to fly across it at 800 km per hour, but looking down from the airplane window it is clear why you would never want to (crash) land there. Most of the continent is about as inviting as the moon: red earth and scrub as far as the eye can see. No roads, just a few tracks. Hardly any signs of human activity – and most of the ones you see are pretty destructive. However, as soon as your flight approaches the coast the picture changes. Wide beaches, long, rolling waves. It still looks like a godforsaken, empty landscape, but your conditioned Western mind provides the lounge chairs, ice creams and long drinks.

Once you’re down in Sydney Airport, things are different, of course. Aussie culture can be more businesslike and down-to-earth than any other. Things are managed curtly, but friendly and quite efficiently – period. Which is OK if you want to get to your residency as soon as possible and get down to work, which we did. The major obstacle to drive our rented vehicle into the mountains was the fact there weren’t any maps. It was too expensive to use our Europe-based phone app, and the locals didn’t seem to need any – so gas stations did not sell them. Strange for a country where people still get seriously lost every year and sometimes even die on tracks in the outback…

It was only after our residency that we had time to take a (much too short) look at Sydney. It’s a charming and welcoming city, on a beautiful location. The people we met were open and friendly, Chinatown is full of good smells and great food, and the harbor in the evening has a true fairy-tale beauty. Small wonder that people from all over world – China and South-East Asian countries in particular – are flocking to the place.

Why stereo photographs?

Mels Dees, 22-02-2019

More or less accidentally, stereophotography came to be connected to Australia in my work. Since childhood, I had always been attracted to the silent, frozen world presented by my grandfather’s stereoscope and his tiny (three or four) collection of pictures. They felt so much more mysterious and intimate than my father’s 8 mm films or my family’s colour photographs. So when we landed in Tasmania in 2006, and the huge Russian landscape camera I had brought in turned out to have been demolished by the customs authorities, it did not require a lot of mental exertion to land on the idea. With a bit of trial and error, I managed to construct an aluminum contraption which turned the simple digital camera we still had into a stereo camera of sorts. It did not work for moving subjects, but that did not bother me much.

Presenting stereo material is always a problem. You end up with people waiting in line to peep through a private viewer and pictures getting mixed and messed up, or with a dark room full of people with ugly glasses, staring cross-eyed at a screen. My solution for our show in Launceston in 2012 was to make batteries of viewers, each with a single picture. That way I was able to preserve the private, dreamy atmosphere of my grandfather’s stereoscope. The viewers were made from recycled cardboard material and lenses from cheap toy binoculars. But the effect was quite impressive and I reconstructed the installation for exhibitions in De Meerse (Hoofddorp), Amsterdam and elsewhere.

Using stereo pictures to recreate the spatial experience of the Tasmanian and Australian landscapes turned out to be a good idea. Not only as a semi-vintage knack, but also because it induces the spectator to think about the space he sees. It might make him realize that this spatial experience – maybe all spatial experience – is actually constructed inside his head. Although the image takes on a tangibility that a single flat picture can never possess, it also becomes more ethereal, abstract and dream-like.

For the stereo pictures I created in Tasmania, I almost exclusively used black and white photographs, and restricted manipulation to negative and solarization filters. On the mainland, some 12 years later, I allowed myself the use of colour and computer-generated additions. This complicated the construction of the stereo images considerably. Colour creates depth in unpredictable ways and I realized that adding 3D-elements to a stereo picture is not easy at all. In many pictures I had to construct models in 3d (using Rhino), make a double stereo image and blend those with the background, keeping in mind the camera viewpoint, focus, lighting etc. And even then the results did not always convince (me).

But in Australia I made a discovery that made the presentation of stereo pics a bit less problematic. The standard size of old-fashioned stereoscopic cards is about 90 x 180 mm (the size is limited by the distance between human eyes). This turned out to correspond nicely with the frame of my Ipad mini – which until then I had used mainly to read Dutch papers abroad or foreign papers in Holland. It took only a few hours of tinkering to combine a 19th-century stereoscope (the closed Brewster type) and the case of my Ipad mini into an programmable electronic stereo viewer. Keynote presentation software is all you need to program endless series of stereoscopic pics.

Researching my Primal Nature Project at BigCi

Mariëlle van den Bergh, 20-03-2020

In 2018, at the residency at BigCi, Wollemi

National Park in Australia, I started my research for the Primal Nature Project.

This was an installation I planned to make for a solo exhibition at Museum

Rijswijk and the work would be based on the wild, unspoiled nature of Australia

and Tasmania. I wanted to make a combination of textiles and ceramics, both

materials I have used in previous art works. I had applied for grants, but it

would be months before I knew if the grants, by the Mondriaan Foundation and

Foundation Stokroos, would be awarded.

At BigCi in Bilpin, I went on some bushwalks with Yuri Bolotin and took

pictures and I made drawings of the scenery. The scenery is vast and unique,

and especially in the area of the Gardens of Stone the natural rock sculptures are

miraculous. I tried to get used to the visual language of the environment. The

pagoda’s were strange enough, but these stone flower and plant-like forms would

look awkward and exaggerated in another medium, except in photography.

Apart from drawings I also produced a paper tree, using local materials.

Sticks, branches and tree bark fibres for construction, Cheap Chinese calligraphy

paper as skin, Rae’s cement pigments for colouring and some glue to bring it

all together. During the Open Day the tree was standing in the middle of the

Art Shed and the drawings were on the wall at the first floor.

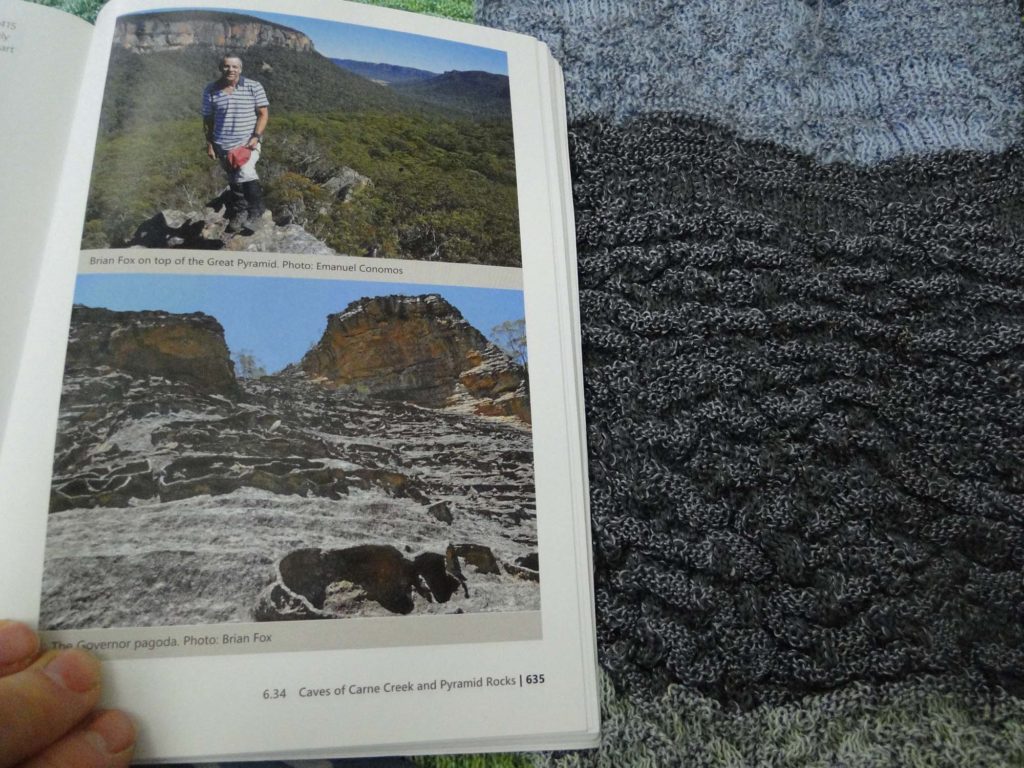

Apart from being a bushwalker and

environmental activist, Yuri Bolotin also explores new regions and tracks in

the Wollemi National Park. Together with co-authors Michael Keats and Brain Fox

he produced more than a dozen books over the years, focusing on new walks,

passes, flora and fauna, caves, aboriginal sites, historical places and

industrial heritage. The books were all in the library of BigCi and at the

disposal of the artists-in-residence.

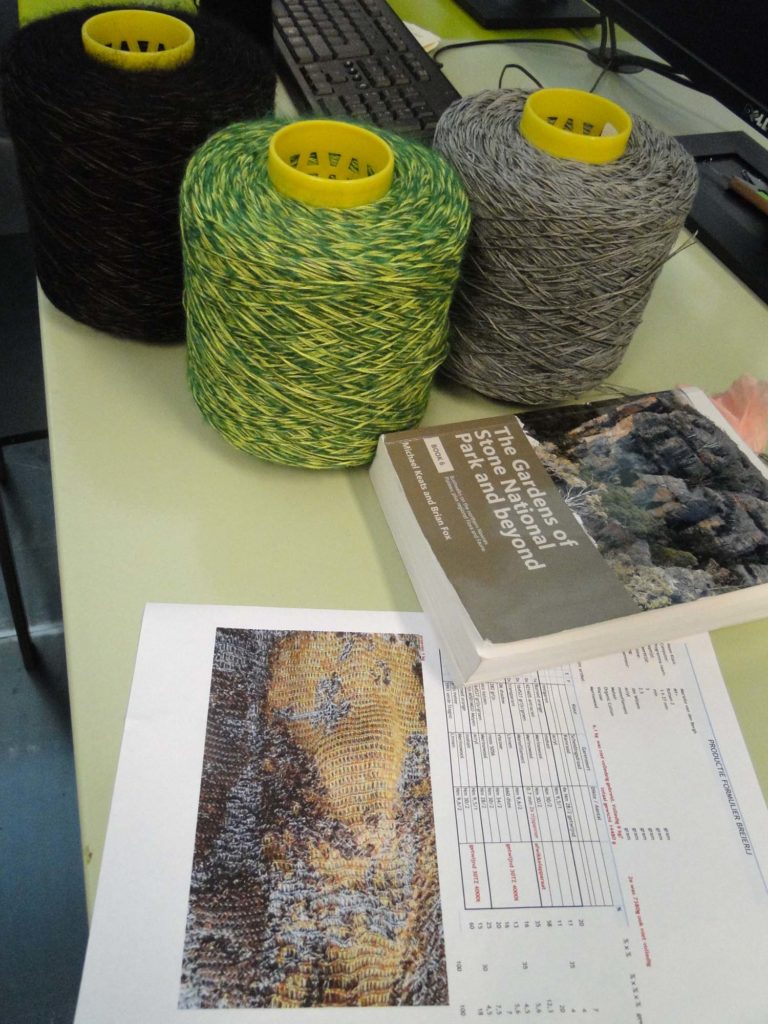

We bought book nr. 6, ‘The Gardens of Stone National Park and beyond’ and it turned

out to be most valuable back home, in the Netherlands.

Working at the LAB of the Textile Museum Tilburg

Half a year later, in the Netherlands, I was awarded both grants, which enabled me to make the work I wanted to do and – very important – on the right scale.

For applying at the LAB of the Textile Museum one needs quite a bit of money and a convincing plan. The Textile Museum has a variety of departments, all with specialists in a different textile technique. For the Primal Nature Project I was going to work at all departments: Weaving, Knitting, Embroidery and Laser-cutting, Braiding and Tufting.

Knitting

I started at Knitting and worked with Jan Willem Smeulders. We knitted on a fine knitting machine and made samples of colour combinations. The pattern is made on the computer and sent to the knitting machine. As a starting point you can use a digital image: a photo or a drawing, that is analysed and reshaped into a suitable image which the knitting machine can handle. To get the right colours, we twined yarns to be knitted. They need to make the right thickness, right individual colour, that will in combination with other yarns make the right colour. Sometimes we also used a very thin plastic yarn, a monofilament.

We also started to work on coarser knitted cloth, working on another knitting machine and using a 0,7 mm monofilament yarn. The coarse cloth then shrunk heavily, creating a textile landscape. This demands quite a lot technical skill, both from the producer and the technician working at the knitting machines. Even the way you twist the yarn will influence if and how the cloth will be knitted. We produced big and long pieces of fabric, based on the colours of the Gardens of Stone, and while they were knitted, they started to shrink and wriggle, which presented quite an impressive sight. As a pattern I used the drawings of the rocks I made at the Gardens of Stone.

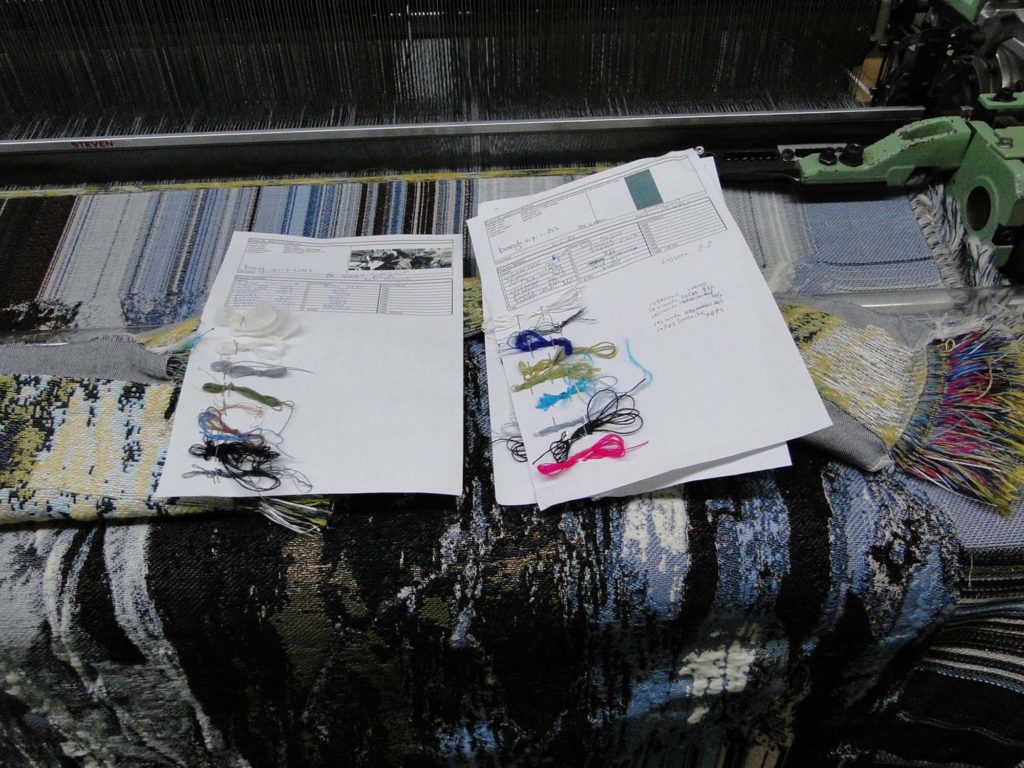

Weaving

I had worked before with product developer Marjan van Oeffelt. The last time was in 2017, on a series of Rocks (Canada). Images are on Instagram: mariellevandenbergh.eu Originally I planned to have the woven parts in between the columns with coarsely knitted cloth. This didn’t work when, at a later time, in the European Ceramic Work Centre in Oisterwijk, I put the samples between the pillars. The textiles, made in different techniques, detonated. I solved the visual problem by sticking to the same technique for the middle piece; knitting in a combination of fine and coarse material. And two separate pieces, a standing and a horizontal rock, that would stand in front of the large middle part. The rocks were made of woven cloth.

Braiding (Passement)

Braiding was a new technique to me and the braiding department had a new product developer: Veva de Wolf. I learnt that there are different methods and different machines. The technique has a long history and has been used for many different purposes, like making cords for uniforms or curtains or decorations on dresses. What I wanted to do was to create vines which would match or contrast with the background. They also should have naturalistic details, like a rough surface, or carry flowers or leaves.

We made cords, in a dominant colour, but assembled from 16 spools with a different yarn each. If you want a dominant brown colour, you use more brownish yarns: some could be cotton, some wool, or acrylic, maybe one would be glistering polyester, just to catch the eye on a shimmer. So you mix colours and types of yarn as if in cooking, when you mix ingredients. It depend on what flavour you want, what you will use as an ingredient. In my case I used, besides the yarns, also rubber, felt (even the rest material after we had done laser cutting) and embroidered leaves and flowers. The other technique is called gimping: you use a cord spinning fast between two points. You can build up the cord by winding a yarn around it, feeding the spinning cord material. We made flowers and extra vines, using fibres (flax, grass, sisal).

Embroidery

I had also worked before with product developer Frank de Wind. His embroidery machine is directed by computer images, which are drawn in a vector programme. The drawing will also determine the routing of the sewing line (which line first, which next, and so on) and one can choose in which pattern the machine will work (which embroidery stitch).

In my case we used water-soluble fleece and foam, to add volume to the material, and organza fabric.

Laser Cutting

Laser cutting is also done by Frank and he draws on his computer the shape and the route the cutter has to take through the material. You can use a lot of different materials. Funny enough, natural felted wool will cause a lot of burned-hair stench while synthetic felt cuts wonderfully. I used long, laser-cut strings of leaves in the installation, but I also used the left over rest material as a core in the braiding of vines.

Tufting

Hand tufting is supervised by Hester Onijs. She usually works on a framed fleece from the back side, shooting loops of yarn through the material. Then the yarn is cut to a certain size, depending on the size of the needle used. One can mix different materials: cotton, wool, synthetic fibres to make the right thickness and the right colours and mix these in order to get the right visual appearance. I used tufting to make the ceramic parts stand out. The tufting made the ideal surrounding edging for the subtly-coloured foam porcelain patches.

Ceramics: working at sundaymorning @ ekwc

Nowadays, the European Ceramic Work Centre

is based in Oisterwijk, in a former leather factory. Artists-in-residence

usually do a residency of three months, which I also did in 2018. At that time

I developed a foam porcelain technique, which I combined with knitted black and

white material – resulting in a material that looked like landscapes.

In 2019 I was offered the opportunity to work at EKWC again for a couple of

weeks. I kept working with foam porcelain and developed a range of colours that

would match the textiles I produced at the Textile Museum. Foam porcelain is a

mixture of components and adding oxides and pigments will influence the

behaviour of the porcelain. To learn how to control the process you have to

experiment a lot. I had transported the three big textile columns to the studio

in the EKWC and hunted for matching colours in ceramics.

Solo Exhibition Oernatuur, Primal Nature in Museum Rijswijk

On Sunday 27 October 2019 the exhibition Oernatuur, Primal Nature was opened at Museum Rijswijk by Australian artist Katy Woodroffe in the presence of the Australian Ambassador Mr. Neuhaus and his wife Angela Neuhaus. Katy, being the one who initiated the Poimena residency in Tasmania when she was head of the Art Department of Launceston Grammar School, remembered our Tasmanian residency in 2006, which had started all my textile works since that moment and which had been so influential in the newest work, the installation Primal Nature.

The show was also the last show curator Anne Kloosterboer made. She had started with the yearly Biennials: altering the Holland Paper Biennial with the Rijswijk Textile Biennial. These are international shows, featuring the latest works in fibre materials, and trends or extraordinary techniques from all over the world. They are always accompanied by an English/Dutch catalogue and many international artists are present at the opening. There also is a market in September. For a meet and greet and networking in the Paper and Textile Art world, I can recommend these gatherings. I myself was a participating artist in 2002 at the Holland Paper Biennial and in 2011 in the Rijswijk Textile Biennial.

www.museumrijswijk.nl

www.katywoodroffe.com.au

The work Primal Nature has been made possible by the financial support by

The Mondriaan Foundation and Stichting Stokroos

There was a variety of activities during

the show, such as an educational table with samples of all the textile

materials and techniques used in the installation, as well as porcelain

samples. The public was allowed to touch everything on the table. There also was

an educational corner where the public could sew their own version of ‘Underwater

Life’, using neckties and little rags I had provided. They could make their own

small exhibition with some ceramic ship wrecks I had made. In three glass showcases

more ceramic ship wrecks were exhibited, surrounded by more Underwater Life,

made of ties and sewn by Outsider Artists and members of the Textile group

STiQS. The museum also provided guided tours and there was a workshop where

waste materials were recycled into small art works.

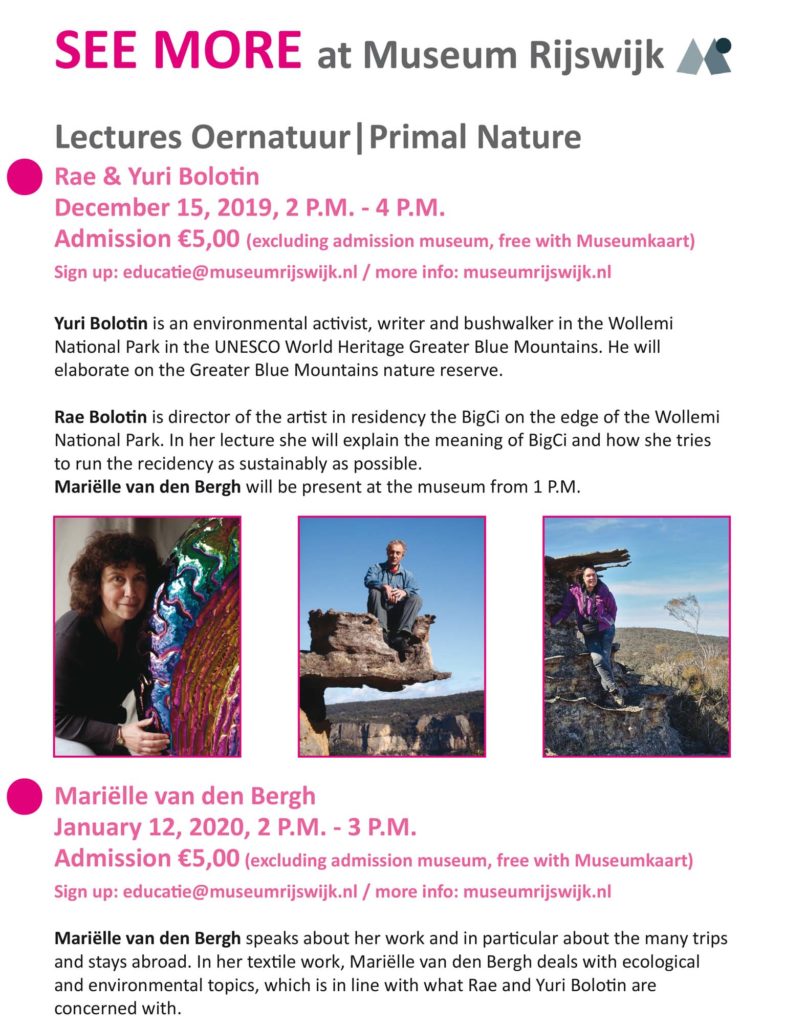

Australian BigCi director Rae Bolotin gave a lecture, recounting how her work

as a sculptor had initiated the search for a bigger studio, which finally

evolved into the creation of the BigCi residency, located at the border of the

Wollemi National Park. Rae showed a variety of mostly international artists and

the projects they had done at Bilpin over the past 10 years.

Her husband Yuri Bolotin’s lecture was about the special natural environment of

the Blue Mountains, the Wollemi National Park and the Gardens of Stone. He

explained how unique this region is in the world, how long it took nature to

shape it and how vulnerable it is. The mining industry and even the Australian

government seem to prefer a quick dollar over protecting the area, as the

aboriginals have done for generations.

www.bigci.org

My own lecture, at the end of the

exhibition, was on ‘Residencies and the influence on my artistic work’.

In BBK Magazine, March 2020 (Visual Artists Union), two articles were published

about the lectures.

There are also two reviews of the show online:

Chris Reinewald on the website of Textile Magazine Textiel Plus:

https://www.textielplus.nl/artikelen/expo-oernatuur-toont-textiele-ontdekkingstochten-van-marielle-van-den-bergh/

Ans van Berkum on the website of Sculpture Magazine Beelden: