Although we have been very busy during the last year, nothing much has appeared in these pages. But we are changing that…

To cut a long story short: both of us (Mariëlle van den Bergh and Mels Dees) had quite a few exhibitions, with ceramics, paper works and the PATAMAP 2021 (an graphic edition of etchings, linoprints, photo and Toyoba prints at the occasion of 40 years Patagonia Studios). More about that you will find further below.

But now, October 2021, we also are on tour again. We decided to go on a residency using a prize Mels won at the Third Ceramic Triennial at CODA Museum, Apeldoorn (a beautiful exhibition nobody ever saw, since it was closed for the whole two months it lasted). The residency we chose was the ICS in Kecskemét, Hungary – first, because they are equipped with a few wood fire kilns, and second, because it was recommended by a colleague we respect a lot, Esther Imre.

After the busy Corona year we decided to do some serious slow travelling to get there. So we stopped over in Kassel, Ingolstadt and Vienna. We saw some artist friends and a lot of exhibitions on the way. Some of the last were quite extraordinary, which prompted Mels to try and make some sense of them in a text.

Strange Exhibitions: Kassel

Mels Dees, 10 October 2021

Even in Documenta years, Kassel is a quiet place. Of course the streets are crowded, but the visiting public is usually made up of introverted, contemplative people – curious, but strangely pensive. After a drink or two, I imagine they will fall asleep in their hotel rooms, dreaming of whatever art lovers dream of.

I remember that, when I first visited the Documenta some 40 years ago, I spent the night in my car. Even if a hotel room had been available, I would not have been able to pay for it. In the middle of the night a traffic cop knocked on my car window. I woke up and immediately started to apologize, explaining that I had come from abroad and there was not a single…

“No, no,” he said, “I just wanted to check you hadn’t died.”

So yes, Kassel might very well be the ideal town to house a museum dedicated to the way we treat our deceased: the Museum für Sepulkralkultur, built on top of the hill where all the exhibition venues are. It overlooks the beautiful, spacious park in the valley. The museum is mainly about historical attitudes towards death – in Europe, Central Europe to be precise. There are hardly any non-European artifacts on show. Imagine how many Documentas could be filled with the answers to the fact that we die from cultures all over the world.

However, the existing collection offers quite a few surprises as well. For the first time in my life, I saw death pictured – not as the iconic lifeless skeleton, but as a process. A beautiful wooden sculpture at the museum shows a dancing corpse with rotting muscles falling from the bones and skin hanging in flaps over the exuberant carcass.

Later, when I looked it up, it turned out that these transi corps sculptures, as they are called, were quite en vogue in Western Europe during the Renaissance. They depicted a deceased person during the transition between life and death and some of them went as far as showing the dead body being eaten by worms. One’s belief in (any) god must be pretty fierce if it survives art like that.

But on the whole, our Western tradition tends to present a more palatable image of death – while trying to make it into a business model as well. We are provided with images as an anchor for our memories, places to go, things to do, rituals to follow and stories to believe.

That used to work, and probably still does, for most people.

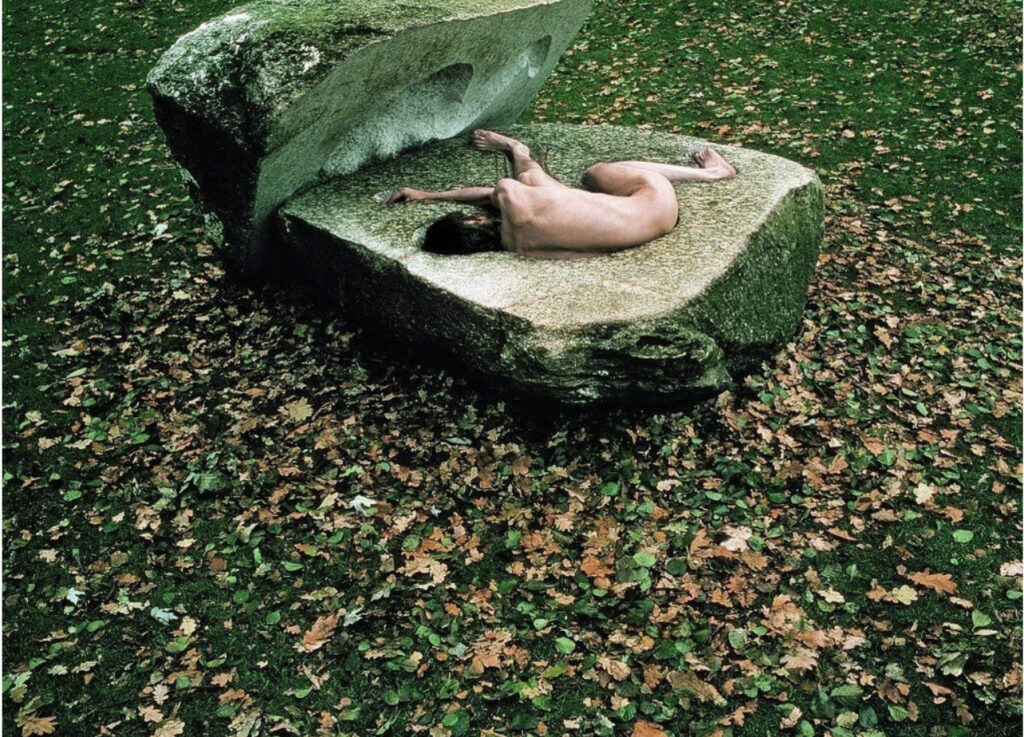

Among more recent artworks at the museum, I find Der Findling, by Timm Ulrichs, the most touching. The title means both ‘The Boulder’ and ‘The Foundling’. The picture is the record of an action performed in 1978, 1980 and 1982, during which Ulrichs stayed inside the stone sarcophagus for up to 10 hours. Ulrichs was a typical ‘action artist’ of 70s, preoccupied with death, film and politics – he had the words The End tattooed on his right eyelid.

But I like this work so much I will insert it into the book I make about my installation Sheltering at the Grenzkunstroute in Aachen, Germany.

The Museum für Sepulkralkultur provides a surprisingly sensitive and level-headed insight into the way we dealt and deal with death in the West.

I can’t think of any other institution that would handle the theme of suicide (in a special temporary exhibition, Suizid) as deftly and carefully as they did.

Weird shows II: Vienna

Vienna’s Museum Quarter is a dense concentration of cultural remains from its Belle Époque: paintings, drawings, architecture and photographs from a time when the subconscious, surrealism, sex and other seriously modern phenomena were being discovered. Impressive, but also rather predictable: Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka, Loos and their carefully canonised works have suffered a bit from overexposure. At least, they are not as unsettling and surprising as they must have been more than a century ago.

But Erwin Wurm’s Vienna exhibition escapes all of this. Its setting is premodern, even pre-19th century, and his work is decidedly post-post-modern. The clash between his works and the museal setting is surprisingly violent, as well as exhilarating and thoroughly satisfying.

It’s fitting that you have to take the Vienna U-Bahn and an endless streetcar ride into the mountains surrounding Vienna to get to the venue: Geymüllerschlössel. An old, renovated and re-renovated mansion sitting in a park with statues left behind after centuries of wars, fires and sheer neglect. Of course, to suit the contemporary public, its name has been simplified into MAK, Museum für Angewandte Kunst – which does not help at all.

But once inside, your attention is drawn by exquisite ceramic stoves – enormous wood-fired heaters that hide their efficiency behind 18th century ornaments, by swirling stairs and hand-painted wallpapers with exotic landscapes. Most of the paintings and objects are dominated by a thoroughly rationalist view of time and space. Otherwise unremarkable views of villages and waterfalls have been made up to date by inserting working clocks in the image.

The museum is almost bursting with clocks and delightful mechanical contraptions. Many of the clocks proudly display their inner workings, including intricate mechanisms indicating the moon’s phases, planet locations etcetera, making it pretty hard to discover what time it is. Other clocks are used to power automated miniature landscapes with waterfalls and playing nymphets. Remarkably, many of them still work.

In short, the museum – as an environment – is a rationalist’s dream of regularity and predictability. Even the surprises are fully mechanised. One of the masterpieces is a filing cabinet made by a master cabinet maker, who managed to hide scores of trick doors, secret drawers and hidden spaces in the dresser. There’s a 15-minute video showing how some of them work.

And then, within this rather meticulously bourgeois décor, there is Erwin Wurm’s ceramic work. Tactile, fleshy, almost uncivilized and blunt. The contrast with the delicate environment could hardly be more complete. Small wonder that the museum’s administrator, doubling as a guide and ticket seller, was more than a bit surly when I asked him what he thought about Wurm’s work.

The pieces look as if they are thrown together in a fairly haphazard way, with casts of body parts – ears, fingers, lips – attached in improbable places. Many seem to be off-balance, with asymmetrical holes and protuberances.

Most works are covered in a thick, pasty ceramic glaze, off-white, blueish or pink. It provides the sculptures with an unhealthy sheen, like the skin of fat people. In other places the shining globs remind you of intestines or bubbling lava.

Erwin Wurm always has had a subversive, sardonic touch, but in this exhibition his anger and fear sometimes seems to outdo his sense of humour. For some people it may be too much, but this work will remain stored in my mind, at least in the subconscious department – in the company of such Austrian luminaries as Ernst Fuchs, Rainer and Nitsch.