WORKING AT THE ICS, KECSKEMÉT

Mels Dees, March 2022

Stipendium CODA Keramiek Triënnale 2021

If you go on a residency as an artist, it’s usually because you hope to encounter a new source of inspiration. A boost to your artistic development. You may look for specialised technical knowledge or expect to meet old friends or new, exciting people and traditions. At least something to kick you ahead artistically and to provide fresh air.

And in order to get into your residency, you write a project plan. You have to. A plan in which you try to align your personal development with the particular artistic climate you expect at your chosen destination.

Not only to convince your host, but also to establish the imagined destination in your private web of judgements and expectations.

But, quite often, then it happens. At the moment you get off the plane or out of the car, you realise that you are in for something entirely different. You were wrong all the time. This is not the place you expected or imagined and you certainly won’t be able to do here whatever you’d planned to do.

This happened to me time and again. At first, I used to panic. The idea of having spent a lot of time and money to work abroad, to get your original plans to be accepted by people you did not know and whose language you sometimes did not even speak – it all might be wasted if you would abandon your plans and, and then… What the hell am I going to do here?

By now I have learned that a new environment, new people, new smells and new art will invariably prompt curiosity, new ideas, and new plans. Arriving at a residency in Xiamen, China (2014), I was completely disoriented by the unexpected steam, clutter and happy noise around me. In order to avoid the heat and the crowds, I decided to get up very early in the morning, at sunrise. I would then catch a random bus at the station in front of our flat (I could not read the destination anyway) and ride it until I started to doubt if I could ever find my way back. Then I would walk home, which usually took a few hours. On the way I took pictures of anything that caught my eye, if possible I would talk to people and find out what was going on. This resulted in fascinating stories and a photographic cross-section of the Xiamen community, which made up a significant part of our final exhibition there.

But Kecskemet would be different, I thought. The ICS is a venerable (50 years!) institution that survived political changes in Hungary and stayed true to its initial goal: ceramics. And that is why we chose to go there. Wood-firing ceramics has become virtually impossible in Holland – understandably, because of the environmental issues (smoke, microdust and pollution in an already overcrowded country). But Mariëlle and I fell in love with the process years ago: it’s one of the rare social events in an otherwise solitary profession and the results are often surprising – another word for unpredictable.

So I wrote down solid plans long before we went – even to my own sceptic ears they sounded pretty convincing:

I want to create a series of ceramic works that encompasses the interests and obsessions of (almost, but not quite, not yet) a lifetime’s work in various media, using:

- The abstract measures, forms and volumes we use to interpret the natural world around us and shape our predictions and responses – from platonic bodies to the architecture of proteins;

- The tactile imprints and shapes of man’s hands and other body parts, that are so important to our contact with and handling of the material world;

- The tools we use, which are empowering and elevating us – as well as thoroughly threatening our existence and the life of our fellow creatures.

Combining these themes in ceramics will, I hope, keep the concept from becoming too formal. It might help to use imperfect, natural clay bodies, and encourage the coincidences inherent to wood-firing.

In hindsight, this is all more than a bit overambitious and pedantic. It might be pretty close to what I want to do in life, but it is not a workable programme for a two-month residency in a provincial town in Hungary. As usual, I only realised that as soon as we arrived.

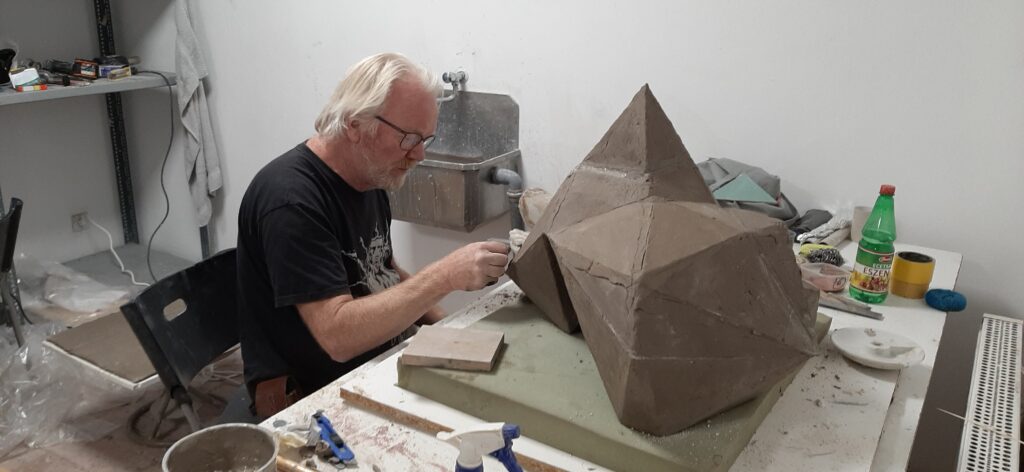

I tried out several solutions, such as taking walks around town and writing about exhibitions we saw on our way to Hungary (see below). Other escape plans included talking, drawing, cooking meals… And then I decided I had better start by pinching the available clay. I started by creating abstract forms – the regular polyhedra – they are both straight from nature and the seeds of human thought. I had done some of them in clay before, but this time I wanted them to be much larger and more perfect – less obviously man-made. Making plaster moulds, as I did in the past, would be too messy and unwieldy for the studio in Kecskemet. But then, in a corner of the storeroom, I found some old pieces of plasterboard.

I managed to develop a technique to cut the necessary polygons precisely and connect them into spatial constructions. The board’s paper cover helped to build crisp shapes and the plaster absorbed the water from the clay, just as it does in massive plaster moulds. The result had just the right amount of irregularity to keep it from being completely dead and abstract. After doing some platonic bodies, I decided to build some old favourites, such as the rhombic dodecahedron and the polyhedron shown on Dürer’s etching Melencolia. Finally I used the remaining pieces of plasterboard to construct a random irregular form. It turned out so complicated and ‘unceramic’ that the oldest, most accomplished ceramic artist at the Kecskemet centre predicted that it could not be fired in one piece. Luckily it did…

Another source of inspiration was found on the daily open market in town. Apart from fresh mushrooms, peppers and other vegetables, there was a stall selling beef tripe: the skin of cow stomachs. The flexible tissue had an intricate regular pattern – both very regular and naturally flowing. Its smell was a bit less appealing, but I took one to the studio. The tripe was too soft and damp to use as a direct mould, so I cast a plaster mould from it. One problem was that the tripe contained so much water that the plaster refused to dry, and another was that all (female) artists working in the studios near my experiment complained about the smell. I had to move the entire installation to our own courtyard and finish the work there.

We fired the final results (after bisqueing and glazing) – the first batch in one of the wood kilns at the centre and a second batch in a soda kiln. As usual they were almost 24-hour events, hard work with friends bringing food and drink. The first firing was relatively quick and successful and produced some excellent stuff, but the soda kiln gave us quite a few problems. As part of the kiln flue had collapsed and obstructed the air flow, we could not get the temperature up after the soda injection, and part of the ceramics were reduced so heavily that the surface turned into a matte black. I decided to refire them at home, and see if I could rescue the glazes.

Almost every object I made in Kecskemet was to be combined with other materials. Other pieces were meant to be part of one or more extensive installations. Some of these have taken shape over the past months, others will follow…