As a result of the Corona Crisis during the spring of 2020, we saw our stay at SPAR (St Petersburg Art Residency) morphed into a Virtual Residency (see https://virtualresidency.p-10.ru/author/mels-dees/ for our contributions). That also resulted in an Online Exhibition. If you want to see it – “Transpositions III: Mind The Gap” can still be found in the SPAR archive. Just scroll left on the main page of their site. Recordings of their public program events are available as well: https://virtualresidency.p-10.ru/whats-happening-here/.

However, we were not content to sit still behind our screens. Despite the travel restrictions we managed to secure not one, but two residencies in the North of Europe: a very short try-out stay at Natthagen in Norway (https://natthagen.no/) and a regular five-week residency at Guldagergaard in Skaelskor, Denmark (https://ceramic.dk/).

Art and mushrooms in the North

Mels Dees, 27 – 10 – 2020

Travelling towards the Norway ferry at Hirtshals, we had a few days to spare. And as one of our favorite museums, the ARoS Museum of Modern Art (with its spectacular roof promenade by Olafur Eliason) was in the middle of a Covid hotspot, we decided to look elsewhere.

It was not easy to find, but the Skovsnogen Art Space turned out to be an unusual place, rather unkempt and without any of the usual suspects like Rodin or Giacometti – or Kirkeby, for that matter. There is no guide, no fixed entrance. You can determine your own entrance fee and there is no Gift Shop to pass when you want to get out. The Skovsnogen Art Space looks like a relic from the 70s or 80s, and that is probably exactly what it is.

I

In some places the Skovsnogen Art Space looked like an artist’s workshop or a weird holiday camp, in others like a dump. Yet it was quite an adventure to walk through – impossible to predict what you were going to encounter next. Which is exactly what makes you want to go on.

Not all sculptures in the ‘workshop’ were perfect or even finished, but the atmosphere was one of medieval dedication. Here and there, there were rather droll and amateurish pieces, but the unpretentious surroundings made them more interesting and sometimes their patina or decay lent them a certain dignity. I know from experience it’s not easy to react to and compete with nature if you work from your studio. So creating sculpture in situ seems like a good idea. At least it saves you the shock of seeing your piece’s size cut back to outdoors dimensions.

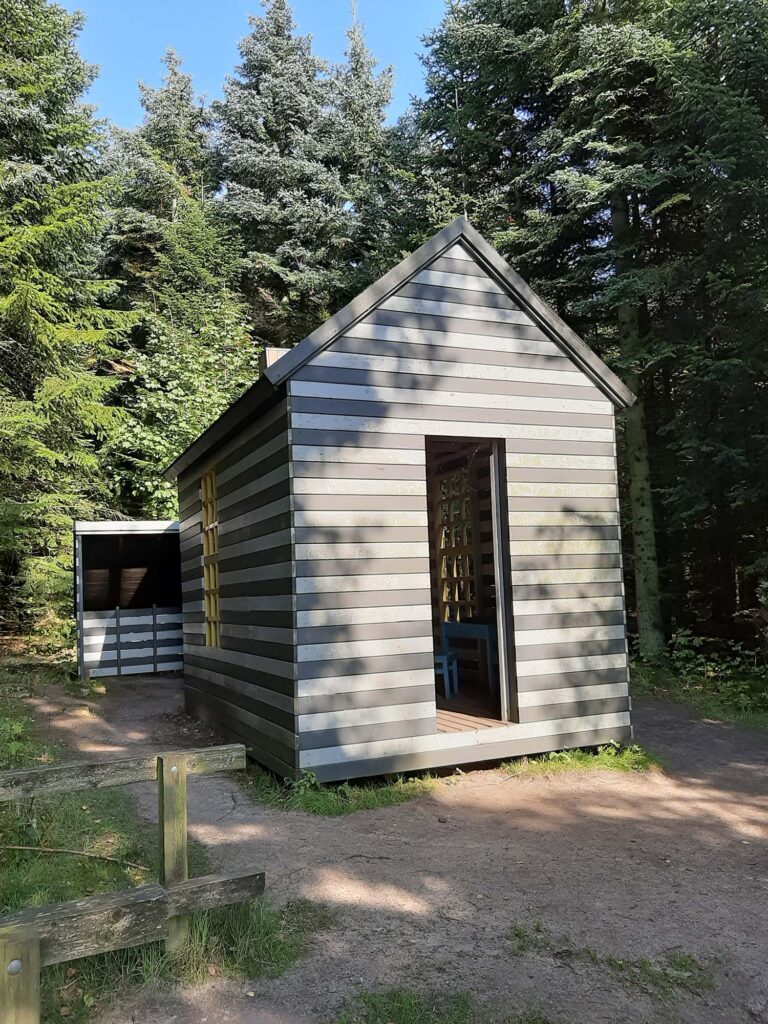

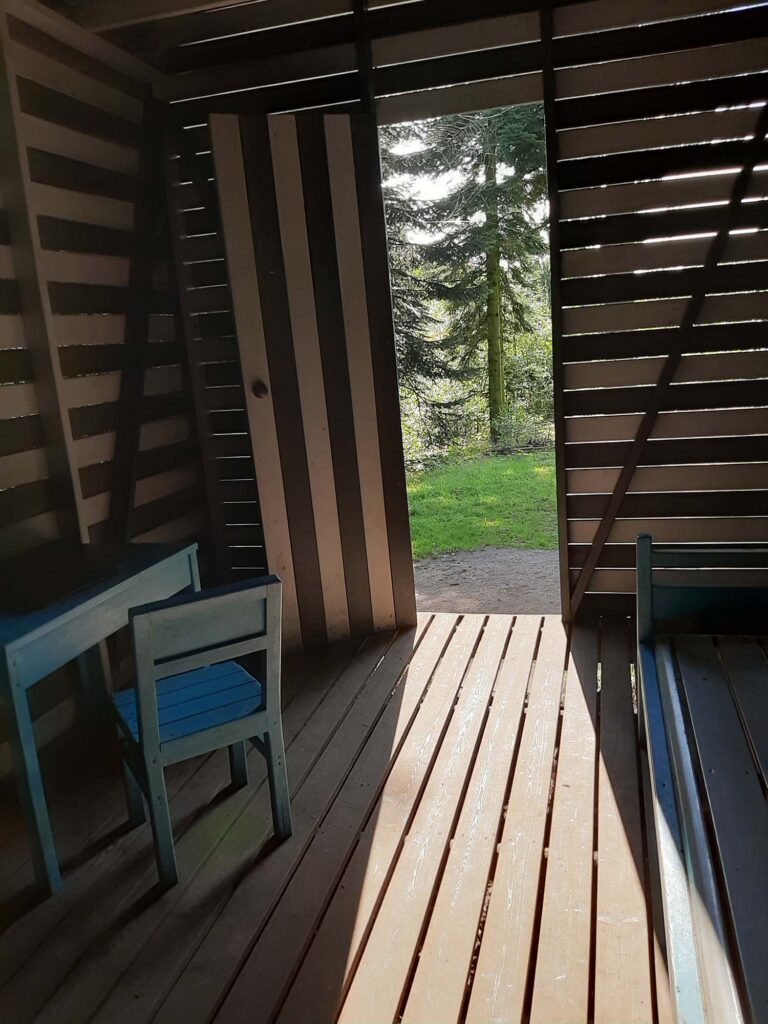

Of course many artworks were well thought-out and executed. A good example was Walden, (too) obviously inspired by Henry David’s Thoreau’s famous book about a year’s stay in a wooden hut on Walden Pond. His account is also “a personal declaration of independence, a social experiment, a voyage of spiritual discovery, a satire, and—to some degree—a manual for self-reliance” (Eiderson). The 3D-version of Thoreau’s hut was precise and charming, but lacked the original’s layered meanings and romantic ideas – still, it provided an exquisite sense of deja-vu.

Quite a few works were so dilapidated that it was quite an effort to reconstruct how they had looked or what they were meant to mean. Strange enough, that did not reduce the pleasure of exploring: it goes to prove how much art-viewing is nowadays approaching archaeology or simply puzzle-solving. At what state of decay does an artwork stop functioning, i.e. when does it cease to be a work of art? (Leaving aside the question what insects and other animals, or aliens descending to earth in an aeon or two, will think of our art…)

A counterpoint to all this anarchistic turmoil is the cheerful construction by the professional playground designers Monstrum. It’s a sensible sculpture for kids and grownups, beautiful, cleverly made and well-kept. Very Danish, if you ask me. Good, clean fun – nothing that can hurt or offend anyone, physically or psychologically. Then again: it does not move you deeply either. Very Danish, indeed.

Then there are two artworks that do not really fit in. Rather harsh-looking concrete structures, one looking like a brutalist communist factory, the other like innocent street furniture. That first impression is deceptive, however.

The ‘factory’ turns out to have no other product than safety and warmth (in a shelter with a simple woodstove) and peace and quiet (in a kind of meditation room).

And what looks like a small group of purely functional steps turns out to be remarkably ambiguous: yes, it is a means to get higher up on the slope – but once you are there, it morphs into an Olympic podium, with the number one place slightly higher than the second best (to the right) who stands again higher than the third place to the left. An icon of competition, you could say.

As you must have noticed, I inserted some portraits – mushroom portraits – between the high and low art we encountered in Skovsnogen. In the first place just because we found them there. And mushrooms interest me, especially if they taste good. Also because they are among the most beautiful natural structures you are allowed to see and photograph without paying for it. You must be a trained mycologist to be able to name them accurately, but it’s not hard at all to enjoy them. So I show them here, most of them unnamed.

The same goes for the titles of artworks I included, as well as the names of their creators. Because of the scarce and incomplete information, but most of all because I felt I did not need them to enjoy the works, I just did not bother. Sorry for that, but it is also (meant as) a compliment.

Norway residency 2020

Mariëlle van den Bergh, 3-10-2020

In the third week of September 2020 Mels and I arrived at Natthagen, in Julussdalen, about 150 kilometers north of Oslo.

It was the inaugural residency at Natthagen, an artist’s iniative set up by two Norwegian artists: Trond Einar Solberg Indsetviken and Robert I. Khoury, who is from Lebanon. We knew about the residency through our mutual friend Kitty, who tipped us and since we were scheduled to do a ceramic residency at Guldagergaard in Skealskor, Denmark in October, we thought we might as well make a detour to Norway first. Mind you: this all happened during Corona times and we had to travel with letters that invited us to do artistic work at both locations. The Danish authority at the Color Lines Ferry read it all and said that we had to go 10 days in quarantine at Natthagen. No problem, as it is in a remote area with only 6 houses, in the middle of a fairy-tale wood, in full autumn colours by then.

I admired the guys, who had had the guts to start this residency, inviting foreign artists, while half of Europe was facing the Second Corona Wave and borders were almost closing again, regulations were tightening, and even the usual crowd on the ferry (staff and truck drivers) were a bit out of their normal behaviour, looking puzzled over their obligatory face masks.

Natthagen means in Norwegian “Night Garden” and indeed there is a small patch on the vast estate, where in the remote past the lady of the house tended a garden with flowers that bloomed and gave off a bit of light at night.

The estate is on a vast patch of land, containing woods, pastures, and buildings. The main building used to be a school, which was literally incapsulated into a new modern and comfortable building: the living quarters of Robert and Trond E and where visitors are received, and symposia and workshops are organised as well. We stayed in a kind of cosy wooden cabin, a Hans and Gretel house, which is called Gamalstu. We were told that in old times up to 11 people used to live there. It is, as most of the Natthagen buildings, a protected site, so no changes can be made unless there is specific permission to do so. That is also the reason why there is no water and no bathroom in the Gamalstu. We had to walk fifty meters to the main house, where we had a bathroom for ourselves. Water was taken in a bucket and since we camp in tents now and then, for us it all added to the plesure of the “outdoors” life. At night we burnt wood logs in the sturdy stove. For Norwegian artists this might be quite normal and it is for us as well, since we heat our studios with wood stoves, but it might be a bit awkward for many other artists. These houses are wooden houses in the middle of a vast forest. Rule number one is to be safe with fire. So burning a romantic candle might be a bad idea and leaving things unattended on the electric stove as well.

Profiting from a couple of sunny days at the start of our residency, Trond E and Robert took us on a tour through the woods and it was enchanting! The beauty and spaciousness were breathtaking. The deciduous trees were turning into their autumn colours and various lichen were spread in a thick carpet. We picked mushrooms to use them for dyeing woollen yarns. Mels of course had other plans with the mushrooms: he preferred the edible types.

Trond Einar Solberg Indsetviken is an advanced water colour artist, with many solo shows in Norway and international exhibitions. Colour is his greatest talent and he conceives all fibres as textiles. He works on all kinds of paper, but very often on rag paper and this is of course made from textile fibres. All his life he had studied the behaviour of pigments, colours and water. When, years ago, he came across plants and mushrooms which could stain fibres and produced colours with a good light stability, he wanted to know everything about it. Right now he is one of the experts in this field and knows many local and foreign mushrooms, plants and lichens

Robert I. Khoury is the head of the Natthagen museum, which is another building on the estate and which in normal times, would be open to the public during the Summer months. Next to the museum is the Art Gallery.

In a sense, Trond E is a local boy, born not far from the place they live now. Part of the museum is dedicated to photos and memorabilia from his family.

But Robert and Trond E as curators have collected much more. The museum boasts a distinctive collection of textile machines and tools, often dating back quite some time. They collect Scandinavian textiles and try to reconstruct how some of these were made and used. Some techniques date back to Viking times; Trond E makes his own wooden tools to perform an old type of crochet and sells them in the Natthagen shop. Both artists are highly skilled textile artists.

Trond Einar Solberg Indsetviken wrote a book on twin knitting: “En fargeglad tvebandstrikker og hans venner” ISBN 978-82-998149-2-8.

Robert I. Khoury specializes in bobbin lace. In Glomdals museum in Elverum, he spent much time studying antique pieces and Christian baptism hats, reconstructing the patterns for historical research and making museum copies, since the silk originals from the 17th century are gone. In 2016, Robert was awarded a Norwegian State scholarship to study lace, with which he financed a trip to Slovenia and Italy, both centres of advanced bobbin lace production in the past.

Right now Robert and Trond E are working at building a collection of lace pieces for the Natthagen Museum. Old bobbins and old pillows, as well as old patterns. They have a collection accumulated by a Norwegian girl, who went to study in Saint Petersburg when the Russian revolution broke out. She bought lace with all the money she had, hid it inside her coat and smuggled it to Norway. As soon as she returned to Norway, the lace started to become industrially produced, and the value of these hand-made pieces went down. She kept all the pieces for herself. Robert got the pieces when the woman died and the family inherited the lace, didn’t know what to do with it and donated it to the Natthagen Museum.

Both curators are collecting textiles from other countries as well. They studied the old band weaving techniques in Syria and made reconstructions of band weaving from Scandinavia. Wooden band weaving cards were found in the Queens ship which is exhibited in Oslo, in the Viking Ship Museum,. So this way of making strong ribbons dates back a long time, but nowadays hardly anyone knows how to do it. Trond E and Robert want to preserve this knowledge and hand it to future generations. So one day Trond E taught me the old technique of band weaving too. I managed to make a long ribbon in a traditional Norwegian pattern and colours during the residency.

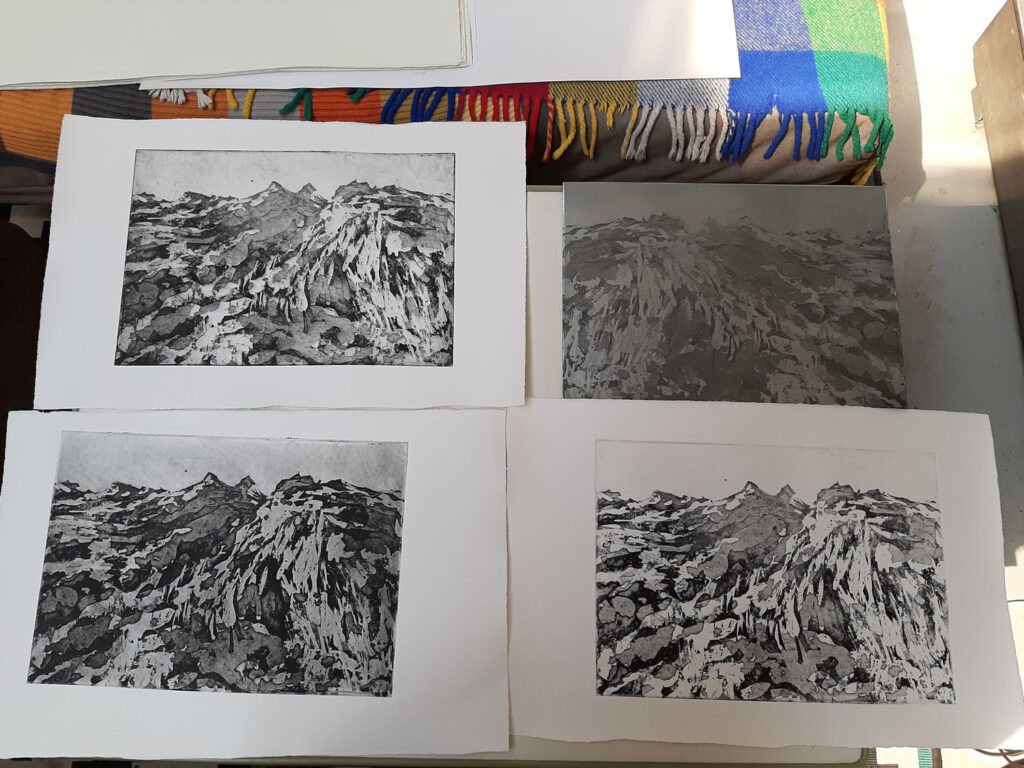

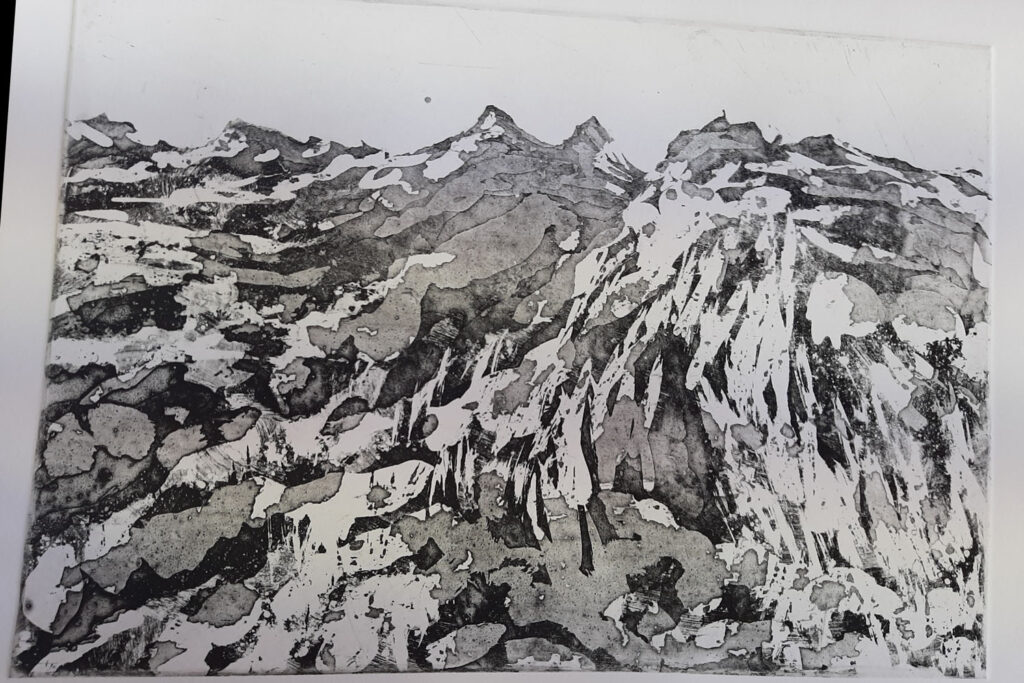

Since Robert was born in Lebanon, they have connections there as well and there are plans to initiate another artists-in-residence, this time in Lebanon. It will be one of the very, very few residencies in the Middle East and since the Natthagen residency is linked to the Lebanese one, these two residencies might prove to become quite important and a successful terrain for artistic cross-fertilization. Another building at Natthagen is the Old Barn. Mels worked here with plaster in preparation for his residency at International Ceramic Research Centre Guldagergaard in Denmark. He chose interesting tools and other objects that were lying around the barn and made plaster moulds from them. In Denmark he will press clay in them and use the ceramic versions in installations later this year. This location is quite primitive, without water, heating or electricity. There is a long work bench now, but practically not much more. However, there are plans to convert it into a studio with a huge glass wall overlooking the surrounding fields and woods, with electricity and therefore light and heating. As soon as Natthagen has secured the necessary funding, the renovation will start. There are further plans for a Textile Studio upstairs. Natthagen has looms, spinning wheels, carding equipment. But this too will depend on grants enabling Natthagen to build this second studio, which could become a very important textile residency in Europe in the future.

Trond E showed us some of his water colour works. One series in particular caught my eye and, being myself a textile artist, I suggested to try to felt one or two of these works. Trond had done some felting, mostly beads with the village children in Lebanon, but he was in for new experiments. So next day we started with a crate of beautifully coloured wool, bubble wrap, olive soap and a table next to the fire. We worked outdoors on the veranda of the main house, since felting is a wet business.

In felting, layers of wool fibres are stacked on top of each other and the last layer, the top layer, has the image or colours you want to show. We looked closely to the water colour to guide us in trying to capture it’s atmosphere. I had done some felting before, but never on this level and never so precise.

We were quite satisfied with the result and some days later we did a second watercolour in this way, differing some procedures and including pebbles as well.

The last felted work was an idea of Trond E: stand outside on the veranda and try to capture the view in felt. The last working day we did just that and I was very impressed by the colouring Trond E did by using his hand carder tools. This was like he was using water colour pigments and created the shades he wanted. He applied them expertly as well in the composition in wool.

All four artists had an end presentation in the white Art Gallery, that is also situated in the Barn. Because of Corona we could unfortunately have the show only virtually.

We like to thank Trond Einar Solberg Indsetviken and Robert I Khoury for the wonderful residency at Natthagen and I am grateful for all the old textile techniques I learned and hope to be able to master and use them in my work in the future. This residency is in one of the most beautiful areas in Norway and we were lucky to be the first artists in the Natthagen residency.