Categorie: Uncategorized (pagina 2 van 2)

From Launceston to Bilpin

Marielle van den Bergh, March 2020

Tasmania

In 2006 we went to Tasmania for the Poimena residency at the Launceston Grammar School in the second city of Tasmania: Launceston. The artist and head of the Art Department, Katy Woodroffe, had initiated the residency. We, Mels, our 8 year old son Quirijn and I, slept in a small unit, which was built to accommodate visiting parents of the boarding school students. We had our meals in a Harry Potter-like hall and had a studio in the annex to a Victorian villa, where the Art School was situated. In order to be able to make my installation of paper, I had written in the proposal, that we would travel through Tasmania to find a characteristic feature of the island, as a starting point for my work.

I also had to gather fibres, which would be a constructive element in producing the paper works.

Katy has a magic wand – she waved it and we were provided with a car. We travelled for a week through Tasmania and fell completely and for ever in love with the island and it’s pristine, unspoiled nature. Especially the giant Old Growth eucalyptus trees (dating from pre-colonial times) are magnificent. Maybe I should say: were magnificent. We found out that these hundreds of years old trees were being harvested at the time (maybe still are?) for the Japanese cardboard industry. Lots of bumper stickers on cars protested against the destruction of these irreplaceable natural resources and symbols of beauty.

For a Dutch girl, with half her native country below sea level, and a natural instinct that is aware of the surrounding water at all times, the sight of the black, charred landscape was quite impressive. But nature was able to regenerate itself, we could see that from the fresh green sprouts on trees and on the ground. However, the carbonised wood, intensely black and spread as far as the eye can see, made us realize what kind of inferno had caused it. My installation at the end of the two months was called Burned Bush and was presented in the Poimena Gallery during our show ‘Double Dutch’. I used Chinese rice paper on a frame of local fibres (tree bark and button grass). I had worked before with these kinds of materials and built quite large installations with it in the past.

The wild primal nature of Tasmania enchanted us, especially in places like Cradle Mountain with its multitude of lichens and ferns, and we marvelled at the mountain ridge of the Walls of Jericho and the orange lichen on the shore boulders in Bay of Fires.

Tasmania revisited

After 2006, we revisited Tasmania in 2018, and found some things had changed over those years. Tasmania has become a popular tourist destiny and is now quite fashionable. Yuppies from all over the world can be spotted in the island’s main city Hobart. Traffic is denser; it is hard to stop on the two-lane roads. More “foreigners” (mainland Aussies) have settled in Tasmania. Katy used to joke that Tassie was usually left off the map of Australia. In 2018 it was definitely a focus point of many people and companies with dubious agenda’s. There is a plan to built a luxury resort in the middle of a nature reserve – the rich will be flown in by helicopter. Somehow it also felt as if a lot of the Old Growth trees were gone. And there was snow at Cradle Mountain, which meant that the accommodation was fully booked and the park was filled with tourists, enjoying the cold winter weather. A bit like a Swiss ski resort in full swing. It looks like Tasmania is being discovered by mass tourism, mostly from east Asia.

The locals are not complaining about these developments – not yet, but many are worried. The best example of a pristine island, featuring breathtaking scenery but with a limited infrastructure – basically a single ring road – is Iceland. In summer, a brief season, the roads are packed with tourists, all driving in the same direction and all meeting each other over and over again during a couple of weeks. There is a discussion among the locals: making money in the tourist industry or voting for a limited access of visitors to the island. During at least part of the year, peace and tranquility are gone.

Back to Tasmania: how to manage large quantities of nature-loving tourists wandering over the wooden floorboards constructed in this beautiful natural reserve? Families of notoriously shy wombats sitting under a small bush may see a thousand people or more passing by on an average day.

BigCi residency in the Blue Mountains

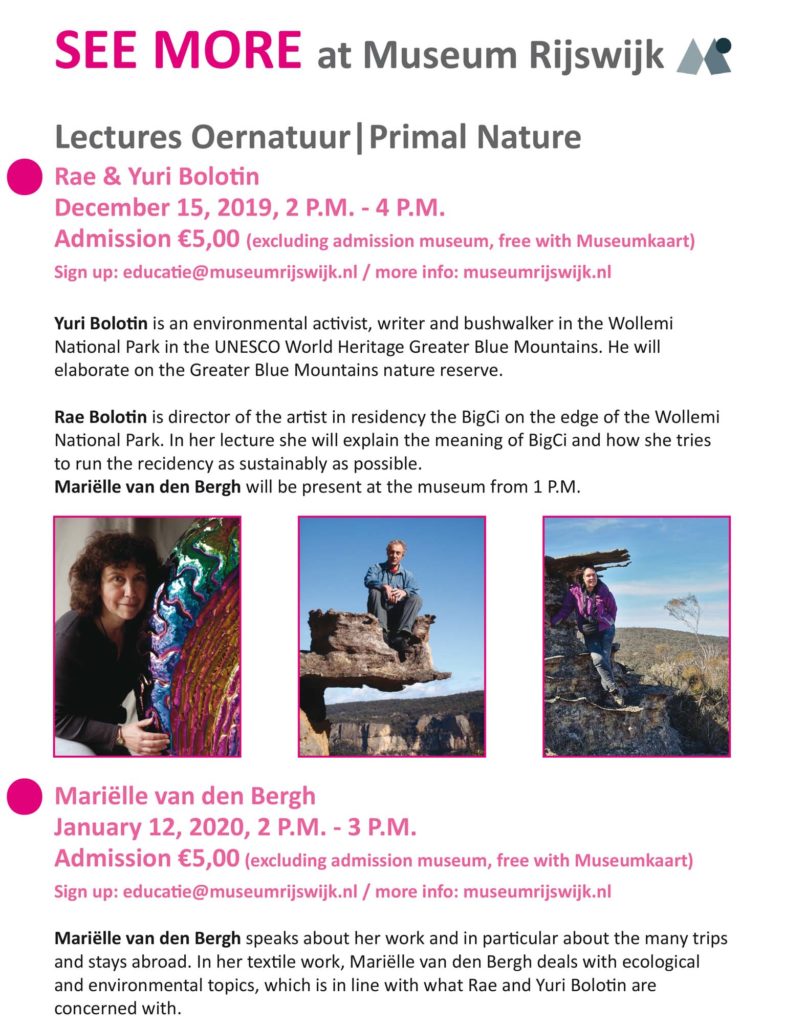

But before visiting Tasmania in 2018 we had been in Australia, at the BigCi residency on the border of Wollemi National Park in the Blue Mountains. BigCi stands for Bilpin Ground for Creative Initiatives and has been founded by director and sculptor Rae Bolotin and her husband Yuri Bolotin, who is an explorer, bushwalker, writer and environmental activist.

Guided by our taste for wild, unspoiled and unusual places in the world, I found the BigCi residency on the Transartists website. Looking at the BigCi website, I found images of the Garden of Stones: an unique region in the Wollemi National Park, where – over thousands and thousands of years – soft sandstone layers were washed away and harder parts, sometimes very thin, curled up into natural sculptures of flowers and exotic plants, all in stone.

The area has also rock pagoda’s, sculpted layered mountains, towering over trees and undergrowth that hide cliffs that are hundreds of meters deep. We had to go there and experience these natural wonders.

We applied as three artists, were selected and went as a family. Our son Quirijn is studying Sonology, Electronic Music at The Hague Royal Conservatoire and wrote his own work plan. My plan was to research the primal nature and use this for the installation I was planning to make for the solo exhibition at Museum Rijswijk, later in the year. The installation would be made from textiles and ceramics and I was granted fundings by the Mondriaan Foundation and Foundation Stokroos. These awards made a big difference, because in Australia you realize that scale is an important requirement in artwork, based on this environment. The art work had to be big and as overpowering as I could make it.

BigCi consists of two buildings, located at the border of

the Wollemi National Park: you only have to cross the dirt road. The main

building is called the Art Shed and is a sober, but extensive multifunctional

two-story building. At the ground level there is the communal studio space, and

at one side the kitchen, bathrooms and Rae’s office. At the back of the

building there is the library and multimedia room. The second level houses the

rooms for more residents. The Art Shed has a very big roof, where rainwater is collected

and directed to two big water storage tanks. The roof is also fitted out with solar

panels, to generate electric power. In an area like this, one has to be

independent and make optimal use of natural resources.

We were, however, located in another building: the Barn, this being a cosy

wooden cabin, with a kitchen, bathroom, a big space where we all could work and

two bedrooms upstairs. This building, which provides a lot of privacy, is often

used by composers.

Rae and Yuri live down the road. On their land is a small

lake, lots of trees, rocks, an abandoned sauna built by early Finnish lumberjacks,

and some of Rae’s breathtaking sculptures.

Rae selects the participants for each month long residency quite precisely,

fine tuning the mix of artists to make an interesting group, with the right

creative chemistry.

Besides the three of us, we were in BigCi with the Australian artist Glenda

Kent, the painter Terri McFarland (USA) and the Chinese, Germany-based artist

Yiy Zhang. Yiy had won an award and was on an exchange programme with the Red

Gallery from Beijing.

The artists-in-residence

Australian artist Glenda Kent usually works with glass, building installations and figures from glass shards. She won the Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize with a cute Teddybear, its ears are shards sticking out of its head. At BigCi Glenda focussed on a rather disturbing natural phenomenon: some trees in the bush are damaged by a beetle, the emerald ash borer, which eats the wood just under the bark. It leaves beautiful patterns on the skin of the tree. Glenda took rubbings and made moulds of an engraved wooden trunk. She also dyed paper with natural colours and used sun light to work on it.

The mould was to be used for glass works later at home.

http://australianphotographcollector.blogspot.com/2017/05/glenda-kent-glass-artist-at-work.html

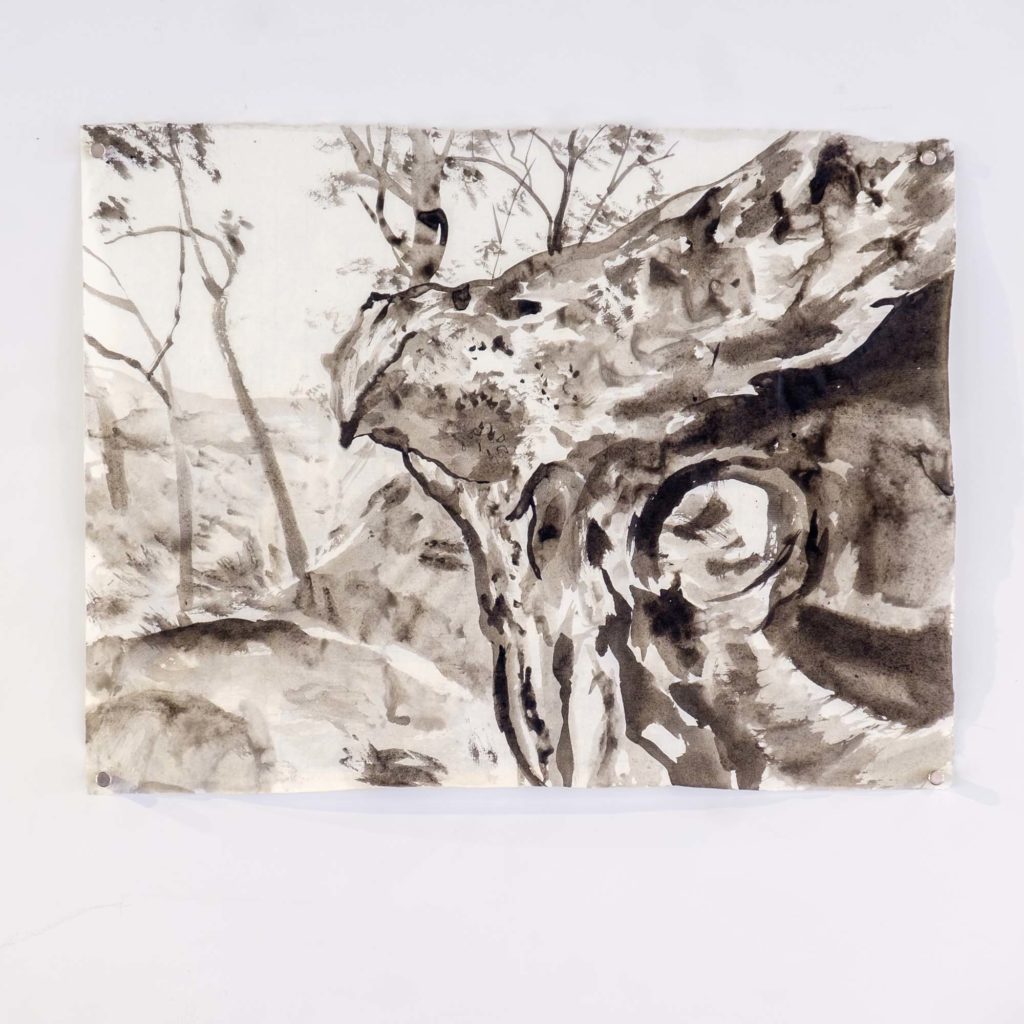

Terri McFarland is a landscape painter, with

a background as a garden designer in California, USA.

She had been on a residency in a breathtaking spot in Norway, making small

paintings of the sea with scattered islands in special sunlight. One day during

the residency, Terri, Mels and I drove out for some time to a valley featuring

huge cliffs. Mels roamed around, taking pictures and taking risks, of which I

was oblivious, since Terri and I were sitting still, making watercolours of the

scenery. We were looking at a rock wall of a few hundred meters height at the

opposite side of the valley, with trees of maybe forty or fifty meters high.

The sun was setting, deepening the colours in the shadows. Besides the shadows lengthening,

time didn’t exist. We could be sitting in eternity. The scale of the

surrounding landscape was frightening and the realisation of the kind of power,

that shaped these volumes, even more so. http://terrimcfarland.com/

Chinese Yiy Zhang is know for her performances, such as “Lebenslinien/ Sisyphos” (Lifelines/ Sisyphos). She specialises in laborious, nearly invisibly subtle interventions in an urban environment, which she then records. At BigCi she prepared a performance, which she enacted during the presentation at the end of the residency, the Open Day. She sewed a coat, shoes and hat with the leaves of the grass tree attached to them. A grass tree is a another of Australia’s weird plant species: it grows 0,8 to 6 cm per year and can reach an age of 350 or even 450 years. In the performance, called “The Shell”, Yiy sat at a cosy table, drinking tea and reading the paper, while wearing the special grass coat and hat. You can find the film on her website: https://www.zhangyiy.com/

Partner in life, crime and art Mels Dees has written below what his work at BigCi was about. He worked with stereo-photography and computer generated images, based on his photography. While giving his presentation in the library at the Open Day, he told stories about how remains of culture often trigger his mind and creativity. He was very interested in the abandoned town of Newness, an old oil shale mining town in Wolgan Valley, that had been deserted a few decades ago. As a contrast, he used images of the thriving mining town of Lithgow where people are said to be so sure of the everlasting power of coal, that their street lights are never turned off. One of his pictures featured a meteor falling on the main street. The work was immediately purchased by a lawyer who had been fighting the establishment of new mines in the neighbourhood, probably to hang in her office.

Apart from being our son, Quirijn Dees is also a young Sonology student, studying Sound and Abstract Electronic Music in The Hague. He was quite amazed to hear the Australian birds making their natural sounds. If you haven’t heard them in real life, it’s hard to imagine their otherworldly songs. Some birds sound like water running down a plumbing pipe, others make noises like a cockroach with a bad cold. Quirijn had brought his recording device and spent the next weeks running out of the house, microphone in the air and becoming very frustrated because the annoying birds would shut up as soon as he showed his face. However, he managed to get the sounds he wanted, and presented an audiovisual animation at the Open Day, where Quirijn also explained to the public how he proceeded in the production of this work. He called his work: “heavily manipulated and transformed environmental recordings, combined with visual textures captured in the gorgeous environment. Thus creating an audiovisual work inspired by environmental elements.”

Working down under – a residency at BigCi

Mels Dees, 22-02-2019

Australia had already been discovered centuries ago by ‘us’, the Dutch – and some 50,000 years before that by the Aboriginals. But until last year it was the mysterious Southland to me, the place where people walk around with their feet backwards, where trees grow with their roots into the sky, where mammals lay eggs and saltwater crocodiles lunch on tanned bathing beauties.

Twelve years before, in 2006, we had done an amazing residency in Launceston, Tasmania. Nominally Tasmania is of course part of Australia, but the island is far more cosy, friendly and relaxed than the wild and rough mainland. We really felt at home there – it was like an slightly weird, exotic version of our native country – and actually, twelve years ago, we all but stayed there to settle down forever and ever. We’re still not quite sure if it was the right decision to return to Holland…

Mainland Australia is a different piece of cake. Not only does it take the greater part of a day to fly across it at 800 km per hour, but looking down from the airplane window it is clear why you would never want to (crash) land there. Most of the continent is about as inviting as the moon: red earth and scrub as far as the eye can see. No roads, just a few tracks. Hardly any signs of human activity – and most of the ones you see are pretty destructive. However, as soon as your flight approaches the coast the picture changes. Wide beaches, long, rolling waves. It still looks like a godforsaken, empty landscape, but your conditioned Western mind provides the lounge chairs, ice creams and long drinks.

Once you’re down in Sydney Airport, things are different, of course. Aussie culture can be more businesslike and down-to-earth than any other. Things are managed curtly, but friendly and quite efficiently – period. Which is OK if you want to get to your residency as soon as possible and get down to work, which we did. The major obstacle to drive our rented vehicle into the mountains was the fact there weren’t any maps. It was too expensive to use our Europe-based phone app, and the locals didn’t seem to need any – so gas stations did not sell them. Strange for a country where people still get seriously lost every year and sometimes even die on tracks in the outback…

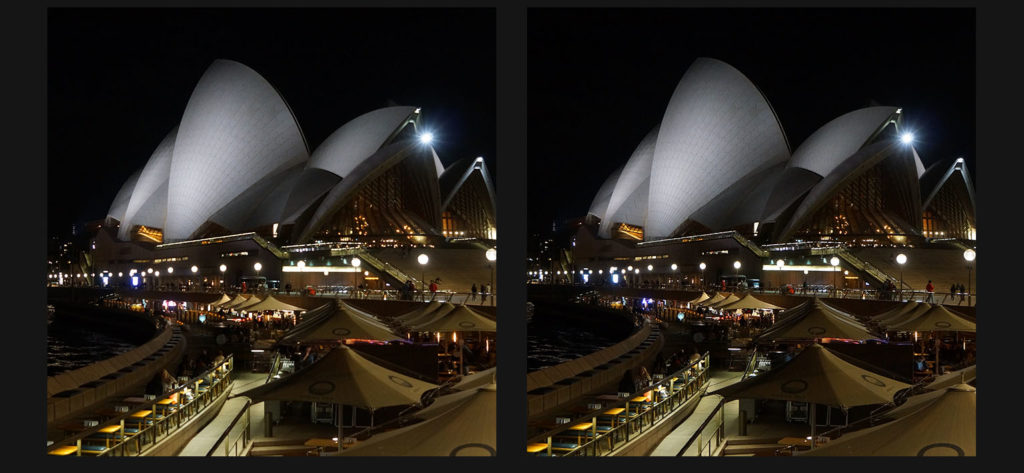

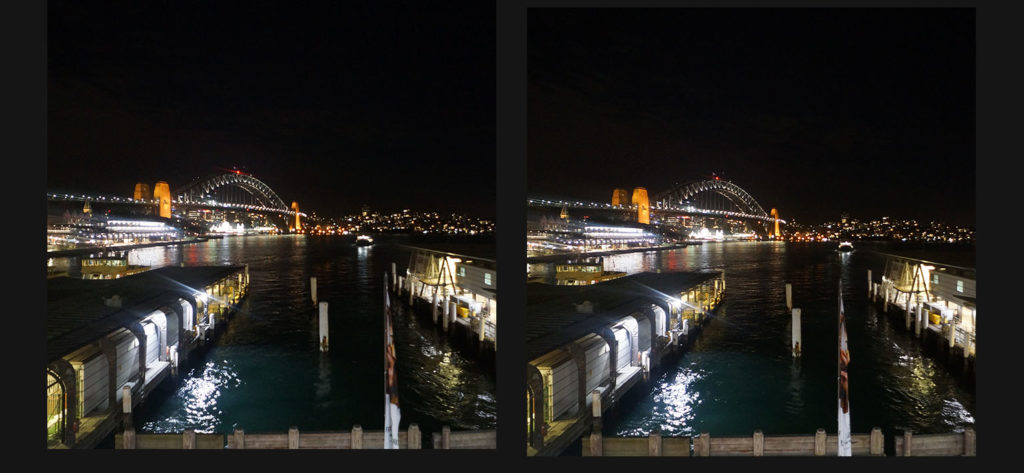

It was only after our residency that we had time to take a (much too short) look at Sydney. It’s a charming and welcoming city, on a beautiful location. The people we met were open and friendly, Chinatown is full of good smells and great food, and the harbor in the evening has a true fairy-tale beauty. Small wonder that people from all over world – China and South-East Asian countries in particular – are flocking to the place.

Why stereo photographs?

Mels Dees, 22-02-2019

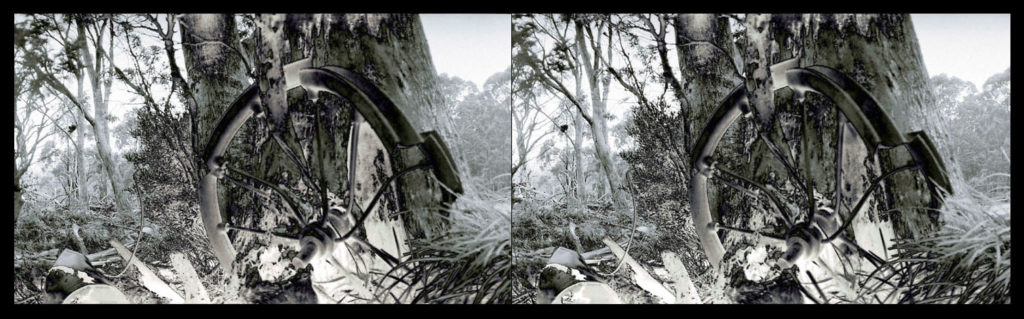

More or less accidentally, stereophotography came to be connected to Australia in my work. Since childhood, I had always been attracted to the silent, frozen world presented by my grandfather’s stereoscope and his tiny (three or four) collection of pictures. They felt so much more mysterious and intimate than my father’s 8 mm films or my family’s colour photographs. So when we landed in Tasmania in 2006, and the huge Russian landscape camera I had brought in turned out to have been demolished by the customs authorities, it did not require a lot of mental exertion to land on the idea. With a bit of trial and error, I managed to construct an aluminum contraption which turned the simple digital camera we still had into a stereo camera of sorts. It did not work for moving subjects, but that did not bother me much.

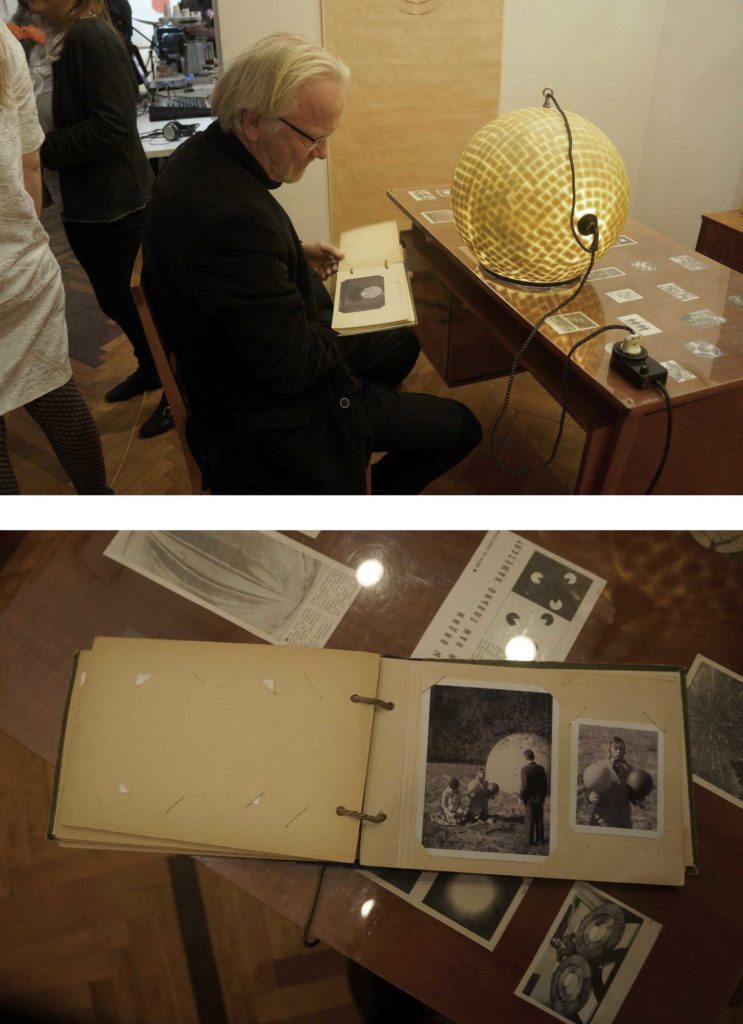

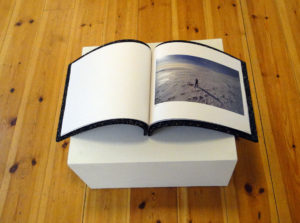

Presenting stereo material is always a problem. You end up with people waiting in line to peep through a private viewer and pictures getting mixed and messed up, or with a dark room full of people with ugly glasses, staring cross-eyed at a screen. My solution for our show in Launceston in 2012 was to make batteries of viewers, each with a single picture. That way I was able to preserve the private, dreamy atmosphere of my grandfather’s stereoscope. The viewers were made from recycled cardboard material and lenses from cheap toy binoculars. But the effect was quite impressive and I reconstructed the installation for exhibitions in De Meerse (Hoofddorp), Amsterdam and elsewhere.

Using stereo pictures to recreate the spatial experience of the Tasmanian and Australian landscapes turned out to be a good idea. Not only as a semi-vintage knack, but also because it induces the spectator to think about the space he sees. It might make him realize that this spatial experience – maybe all spatial experience – is actually constructed inside his head. Although the image takes on a tangibility that a single flat picture can never possess, it also becomes more ethereal, abstract and dream-like.

For the stereo pictures I created in Tasmania, I almost exclusively used black and white photographs, and restricted manipulation to negative and solarization filters. On the mainland, some 12 years later, I allowed myself the use of colour and computer-generated additions. This complicated the construction of the stereo images considerably. Colour creates depth in unpredictable ways and I realized that adding 3D-elements to a stereo picture is not easy at all. In many pictures I had to construct models in 3d (using Rhino), make a double stereo image and blend those with the background, keeping in mind the camera viewpoint, focus, lighting etc. And even then the results did not always convince (me).

But in Australia I made a discovery that made the presentation of stereo pics a bit less problematic. The standard size of old-fashioned stereoscopic cards is about 90 x 180 mm (the size is limited by the distance between human eyes). This turned out to correspond nicely with the frame of my Ipad mini – which until then I had used mainly to read Dutch papers abroad or foreign papers in Holland. It took only a few hours of tinkering to combine a 19th-century stereoscope (the closed Brewster type) and the case of my Ipad mini into an programmable electronic stereo viewer. Keynote presentation software is all you need to program endless series of stereoscopic pics.

Researching my Primal Nature Project at BigCi

Mariëlle van den Bergh, 20-03-2020

In 2018, at the residency at BigCi, Wollemi

National Park in Australia, I started my research for the Primal Nature Project.

This was an installation I planned to make for a solo exhibition at Museum

Rijswijk and the work would be based on the wild, unspoiled nature of Australia

and Tasmania. I wanted to make a combination of textiles and ceramics, both

materials I have used in previous art works. I had applied for grants, but it

would be months before I knew if the grants, by the Mondriaan Foundation and

Foundation Stokroos, would be awarded.

At BigCi in Bilpin, I went on some bushwalks with Yuri Bolotin and took

pictures and I made drawings of the scenery. The scenery is vast and unique,

and especially in the area of the Gardens of Stone the natural rock sculptures are

miraculous. I tried to get used to the visual language of the environment. The

pagoda’s were strange enough, but these stone flower and plant-like forms would

look awkward and exaggerated in another medium, except in photography.

Apart from drawings I also produced a paper tree, using local materials.

Sticks, branches and tree bark fibres for construction, Cheap Chinese calligraphy

paper as skin, Rae’s cement pigments for colouring and some glue to bring it

all together. During the Open Day the tree was standing in the middle of the

Art Shed and the drawings were on the wall at the first floor.

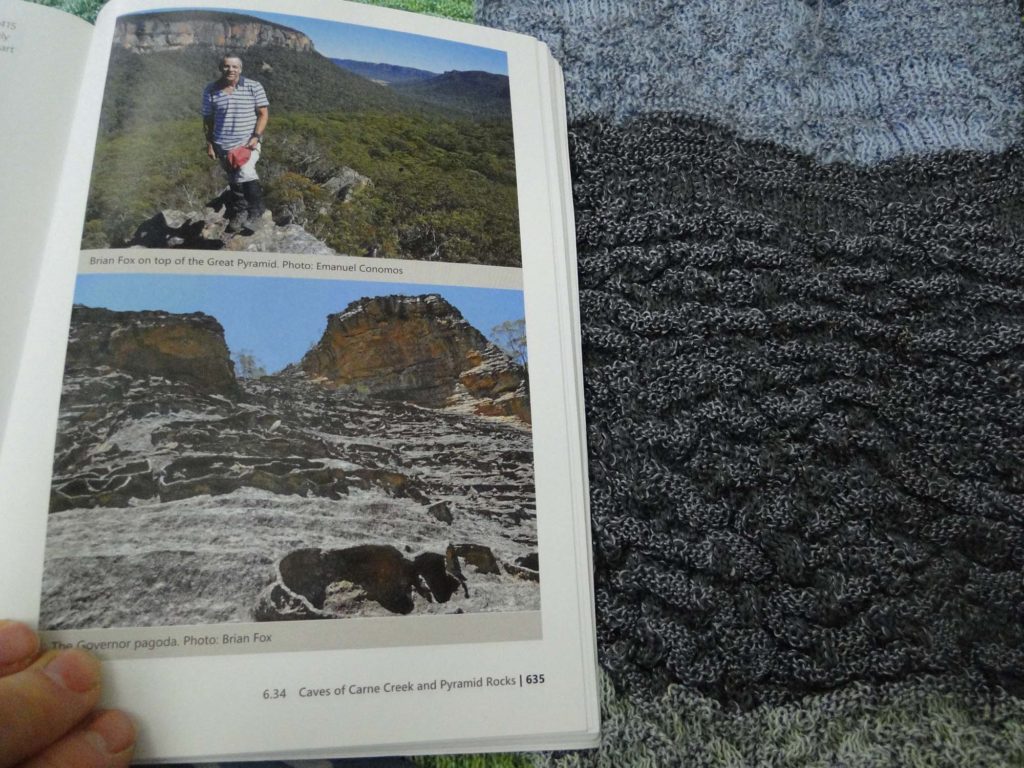

Apart from being a bushwalker and

environmental activist, Yuri Bolotin also explores new regions and tracks in

the Wollemi National Park. Together with co-authors Michael Keats and Brain Fox

he produced more than a dozen books over the years, focusing on new walks,

passes, flora and fauna, caves, aboriginal sites, historical places and

industrial heritage. The books were all in the library of BigCi and at the

disposal of the artists-in-residence.

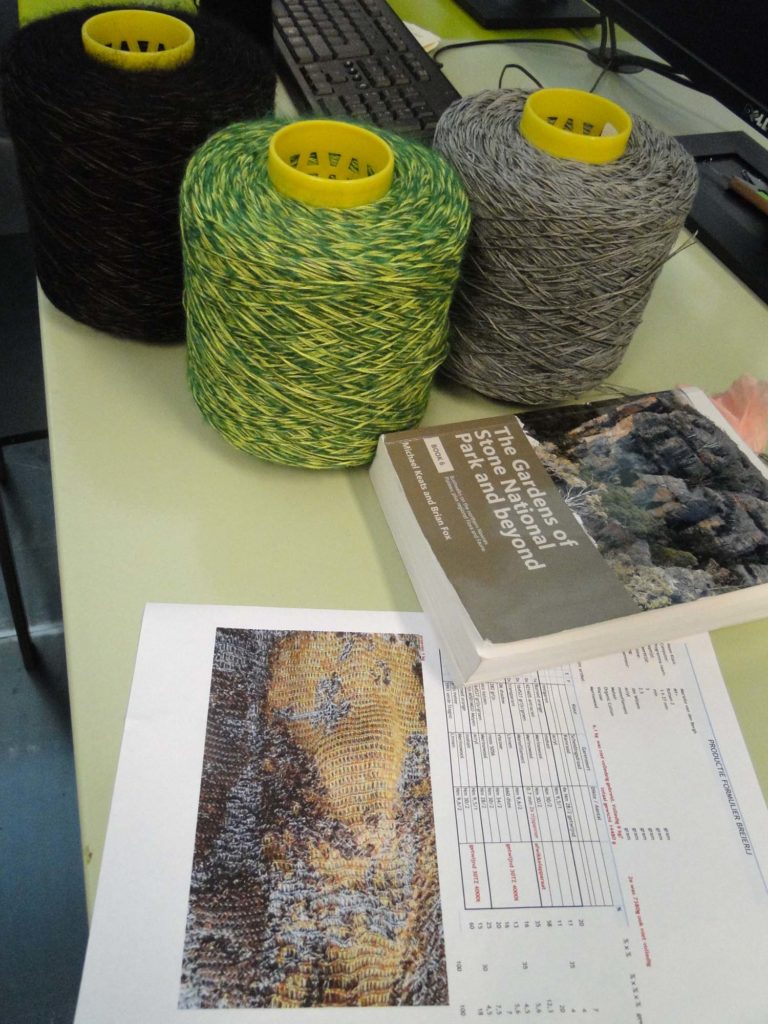

We bought book nr. 6, ‘The Gardens of Stone National Park and beyond’ and it turned

out to be most valuable back home, in the Netherlands.

Working at the LAB of the Textile Museum Tilburg

Half a year later, in the Netherlands, I was awarded both grants, which enabled me to make the work I wanted to do and – very important – on the right scale.

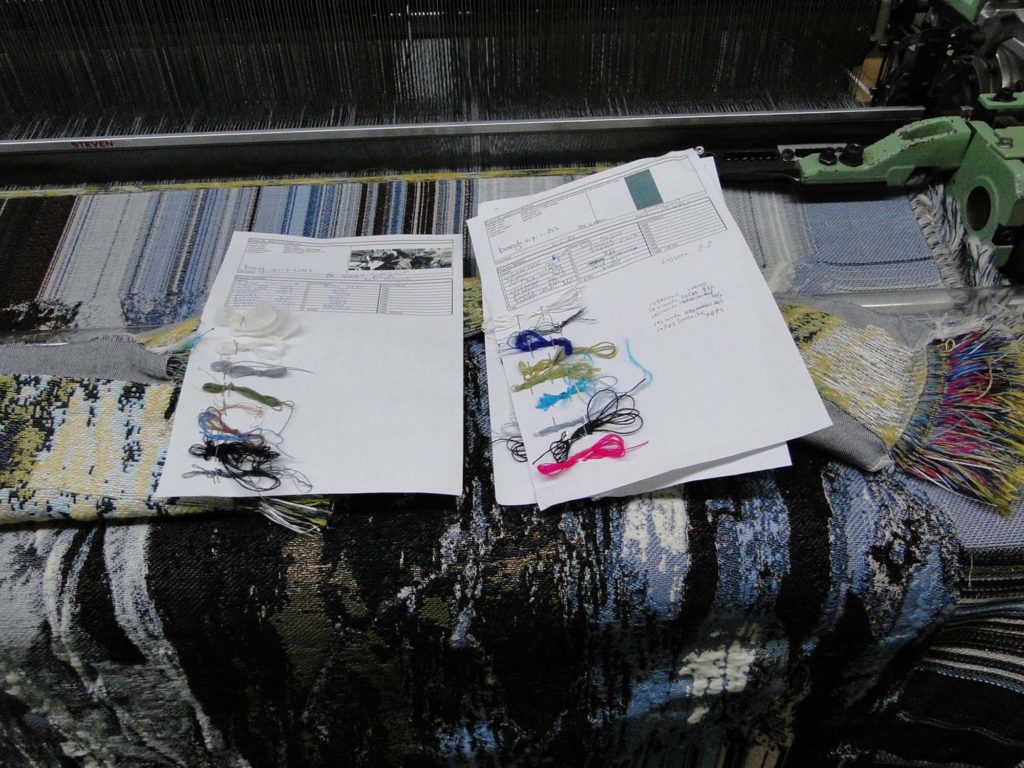

For applying at the LAB of the Textile Museum one needs quite a bit of money and a convincing plan. The Textile Museum has a variety of departments, all with specialists in a different textile technique. For the Primal Nature Project I was going to work at all departments: Weaving, Knitting, Embroidery and Laser-cutting, Braiding and Tufting.

Knitting

I started at Knitting and worked with Jan Willem Smeulders. We knitted on a fine knitting machine and made samples of colour combinations. The pattern is made on the computer and sent to the knitting machine. As a starting point you can use a digital image: a photo or a drawing, that is analysed and reshaped into a suitable image which the knitting machine can handle. To get the right colours, we twined yarns to be knitted. They need to make the right thickness, right individual colour, that will in combination with other yarns make the right colour. Sometimes we also used a very thin plastic yarn, a monofilament.

We also started to work on coarser knitted cloth, working on another knitting machine and using a 0,7 mm monofilament yarn. The coarse cloth then shrunk heavily, creating a textile landscape. This demands quite a lot technical skill, both from the producer and the technician working at the knitting machines. Even the way you twist the yarn will influence if and how the cloth will be knitted. We produced big and long pieces of fabric, based on the colours of the Gardens of Stone, and while they were knitted, they started to shrink and wriggle, which presented quite an impressive sight. As a pattern I used the drawings of the rocks I made at the Gardens of Stone.

Weaving

I had worked before with product developer Marjan van Oeffelt. The last time was in 2017, on a series of Rocks (Canada). Images are on Instagram: mariellevandenbergh.eu Originally I planned to have the woven parts in between the columns with coarsely knitted cloth. This didn’t work when, at a later time, in the European Ceramic Work Centre in Oisterwijk, I put the samples between the pillars. The textiles, made in different techniques, detonated. I solved the visual problem by sticking to the same technique for the middle piece; knitting in a combination of fine and coarse material. And two separate pieces, a standing and a horizontal rock, that would stand in front of the large middle part. The rocks were made of woven cloth.

Braiding (Passement)

Braiding was a new technique to me and the braiding department had a new product developer: Veva de Wolf. I learnt that there are different methods and different machines. The technique has a long history and has been used for many different purposes, like making cords for uniforms or curtains or decorations on dresses. What I wanted to do was to create vines which would match or contrast with the background. They also should have naturalistic details, like a rough surface, or carry flowers or leaves.

We made cords, in a dominant colour, but assembled from 16 spools with a different yarn each. If you want a dominant brown colour, you use more brownish yarns: some could be cotton, some wool, or acrylic, maybe one would be glistering polyester, just to catch the eye on a shimmer. So you mix colours and types of yarn as if in cooking, when you mix ingredients. It depend on what flavour you want, what you will use as an ingredient. In my case I used, besides the yarns, also rubber, felt (even the rest material after we had done laser cutting) and embroidered leaves and flowers. The other technique is called gimping: you use a cord spinning fast between two points. You can build up the cord by winding a yarn around it, feeding the spinning cord material. We made flowers and extra vines, using fibres (flax, grass, sisal).

Embroidery

I had also worked before with product developer Frank de Wind. His embroidery machine is directed by computer images, which are drawn in a vector programme. The drawing will also determine the routing of the sewing line (which line first, which next, and so on) and one can choose in which pattern the machine will work (which embroidery stitch).

In my case we used water-soluble fleece and foam, to add volume to the material, and organza fabric.

Laser Cutting

Laser cutting is also done by Frank and he draws on his computer the shape and the route the cutter has to take through the material. You can use a lot of different materials. Funny enough, natural felted wool will cause a lot of burned-hair stench while synthetic felt cuts wonderfully. I used long, laser-cut strings of leaves in the installation, but I also used the left over rest material as a core in the braiding of vines.

Tufting

Hand tufting is supervised by Hester Onijs. She usually works on a framed fleece from the back side, shooting loops of yarn through the material. Then the yarn is cut to a certain size, depending on the size of the needle used. One can mix different materials: cotton, wool, synthetic fibres to make the right thickness and the right colours and mix these in order to get the right visual appearance. I used tufting to make the ceramic parts stand out. The tufting made the ideal surrounding edging for the subtly-coloured foam porcelain patches.

Ceramics: working at sundaymorning @ ekwc

Nowadays, the European Ceramic Work Centre

is based in Oisterwijk, in a former leather factory. Artists-in-residence

usually do a residency of three months, which I also did in 2018. At that time

I developed a foam porcelain technique, which I combined with knitted black and

white material – resulting in a material that looked like landscapes.

In 2019 I was offered the opportunity to work at EKWC again for a couple of

weeks. I kept working with foam porcelain and developed a range of colours that

would match the textiles I produced at the Textile Museum. Foam porcelain is a

mixture of components and adding oxides and pigments will influence the

behaviour of the porcelain. To learn how to control the process you have to

experiment a lot. I had transported the three big textile columns to the studio

in the EKWC and hunted for matching colours in ceramics.

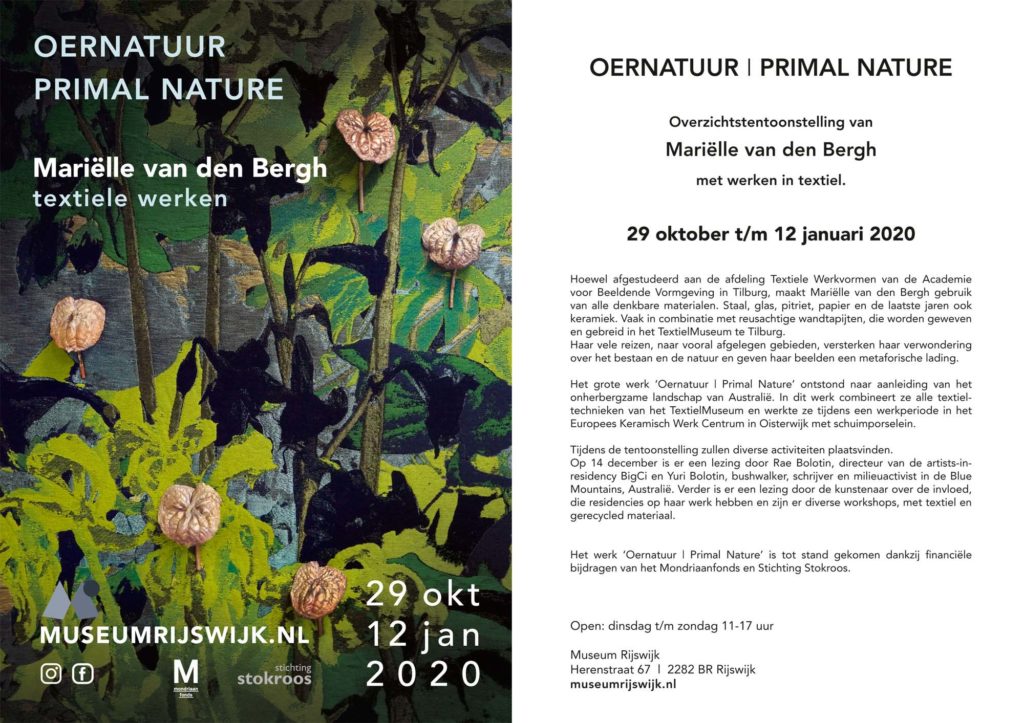

Solo Exhibition Oernatuur, Primal Nature in Museum Rijswijk

On Sunday 27 October 2019 the exhibition Oernatuur, Primal Nature was opened at Museum Rijswijk by Australian artist Katy Woodroffe in the presence of the Australian Ambassador Mr. Neuhaus and his wife Angela Neuhaus. Katy, being the one who initiated the Poimena residency in Tasmania when she was head of the Art Department of Launceston Grammar School, remembered our Tasmanian residency in 2006, which had started all my textile works since that moment and which had been so influential in the newest work, the installation Primal Nature.

The show was also the last show curator Anne Kloosterboer made. She had started with the yearly Biennials: altering the Holland Paper Biennial with the Rijswijk Textile Biennial. These are international shows, featuring the latest works in fibre materials, and trends or extraordinary techniques from all over the world. They are always accompanied by an English/Dutch catalogue and many international artists are present at the opening. There also is a market in September. For a meet and greet and networking in the Paper and Textile Art world, I can recommend these gatherings. I myself was a participating artist in 2002 at the Holland Paper Biennial and in 2011 in the Rijswijk Textile Biennial.

www.museumrijswijk.nl

www.katywoodroffe.com.au

The work Primal Nature has been made possible by the financial support by

The Mondriaan Foundation and Stichting Stokroos

There was a variety of activities during

the show, such as an educational table with samples of all the textile

materials and techniques used in the installation, as well as porcelain

samples. The public was allowed to touch everything on the table. There also was

an educational corner where the public could sew their own version of ‘Underwater

Life’, using neckties and little rags I had provided. They could make their own

small exhibition with some ceramic ship wrecks I had made. In three glass showcases

more ceramic ship wrecks were exhibited, surrounded by more Underwater Life,

made of ties and sewn by Outsider Artists and members of the Textile group

STiQS. The museum also provided guided tours and there was a workshop where

waste materials were recycled into small art works.

Australian BigCi director Rae Bolotin gave a lecture, recounting how her work

as a sculptor had initiated the search for a bigger studio, which finally

evolved into the creation of the BigCi residency, located at the border of the

Wollemi National Park. Rae showed a variety of mostly international artists and

the projects they had done at Bilpin over the past 10 years.

Her husband Yuri Bolotin’s lecture was about the special natural environment of

the Blue Mountains, the Wollemi National Park and the Gardens of Stone. He

explained how unique this region is in the world, how long it took nature to

shape it and how vulnerable it is. The mining industry and even the Australian

government seem to prefer a quick dollar over protecting the area, as the

aboriginals have done for generations.

www.bigci.org

My own lecture, at the end of the

exhibition, was on ‘Residencies and the influence on my artistic work’.

In BBK Magazine, March 2020 (Visual Artists Union), two articles were published

about the lectures.

There are also two reviews of the show online:

Chris Reinewald on the website of Textile Magazine Textiel Plus:

https://www.textielplus.nl/artikelen/expo-oernatuur-toont-textiele-ontdekkingstochten-van-marielle-van-den-bergh/

Ans van Berkum on the website of Sculpture Magazine Beelden:

Information about SPAR

Mariëlle van den Bergh / SPAR 15-07-2017

If you are considering to apply at SPAR, please read this interview Marielle did with SPAR director Anastasia Patsey:

Mlle: What is SPAR?

A: SPAR is Saint-Petersburg Art Residency. It is a programme that is located here, at the Art Centre Pushkinskaya-10. It started in 2012 and basically it functions as any residency programme. Visual and performance artists, as well as researchers, curators, writers, and educators come to Pushkinskaya-10 to live and work here on their projects. The period of stay depends … read more

Artists at SPAR in May and June 2017

We met Suus Agnes from the Netherlands, Marina Ross from USA, Andrea Stanislav and Dean Lozow from USA. Suus stayed 3 months, Marina 2 weeks, Andrea and Dean a couple of months and were actually at SPAR for the fifth time (with their dog). Mels and I stayed 2 months.

Marina Ross‘ project was Care for Beauty. She is an emerging artist from the USA, who is now enrolled in the MFA program at the University of Iowa. Her painting practice currently deals with the (self)image of the female body in the era of social media. The residency at SPAR is part of a larger research and is focused on studying representations of the body through visiting local museums, conducting interviews and creating new works. The works of the series “Care for Beauty” deal with the representation of rituals related to beauty such as applying makeup, looking at oneself in the mirror, as well as such events in a woman’s life as pregnancy and marriage, that often transform the strategies of (self)representation. The artists finds inspiration in the stories told by the female users in social media, staged photo-sessions, editing and careful curation of the visual content, short captions and comments and scenes from the well-known American TV series “Girls”. (Text SPAR)

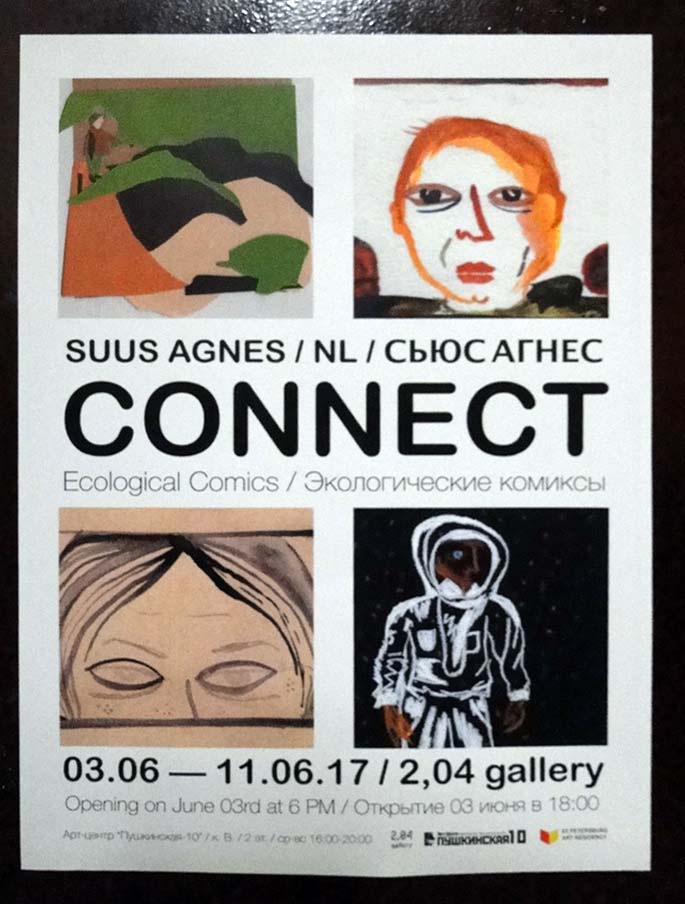

Marina Ross

Suus Agnes’s project is called: Connect: Ecological Comics. Is a human being part of an ecosystem? Are humans simply animals? Do we have an obligation to look after the natural world? There are many ways to answer questions like these. Here in Russia I have spoken to people in remote and rural areas about their connection to the natural environment. I travelled to their houses, communicated digitally, or met them in the city and received a wide range of perspectives: from the problems with forest fires and bee populations, to the joys of living close to nature. A fire-fighter tells me it’s impossible for het to live a city life when she knows large parts of Russia are on fire every year. An Arctic scientist tells me about the methane gas bubbles that are appearing in the Far North due to melting permafrost. He calls for more awareness for the changes around us, so that we can adapt better in the future. A beekeeper explains how humans can both help and damage bees; and a villager speaks about the disconnect between people in cities and in the countryside. Each unique voice is visualised by choosing different artistic materials and colours. This is the beginning of my mixed-media graphic novel, in which I collect stories about the many ways humans are connected to nature. Suus Agnes is a comic artist from the Netherlands. Her work explores the meeting points of narratives, visual arts and environmental education. She completed a Master’s in Creative Non-Fiction Writing (Science Communication) at the University of Otago in New Zealand, and is trained in organic gardening, beekeeping, and nature conservation. Her narratives often investigate the connections between people and the natural world. Her work has been exhibited at galleries, libraries, stores and festivals in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. (Text SPAR)

Anastasia en Suus tijdens opening

Werk Suus

From the SPAR website: American artists Andréa Stanislav and Dean Lozow deserve the status of our ‘annual artists-in-residence’. They came to SPAR for the first time in 2014 and have been developing their work in St. Petersburg and Russia ever since. The multidisciplinary practice of Andréa Stanisalv engages sculpture, installation, video, and public art. She received a MFA from Alfred University, New York; and a BFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The works of Andréa Stanisalv have been exhibited internationally at museums, contemporary art centers, galleries, biennials, and art fairs and are part of institutional and private collections worldwide. She is an associate Professor of Sculpture in the Department of Art, University of Minnesota – Minneapolis and the recipient of numerous awards including, including the Freund Teaching Fellowship, Minnesota State Arts Board Grant, McKnight Artists Fellowship for Visual Arts and many others. Since 2003 she works in close collaboration with artist and art producer Dean Lozow.

Andrea and Dean

Below are some of the activities we were introduced to by SPAR, needless to mention that we had to turn down many possibilities to be at opening of exhibitions and festivals. Just a random selection:

- we went to a concert and exhibition by the Lithuanian composer/painter/photographer/poet Ciurlionis. The event was organised by the consul of Lithuania in the Hermitage.

- Shortly afterwards, there also was a celebration and a concert organised by the Dutch Institute in Saint-Petersburg. Anastasia Patsey introduced us to director Olga Ovechkina, who had invited many Dutch and Russian scientists, business men and people from cultural or otherwise backgrounds.

- At the courtyard of Pushkinskaya-10 a famous Berlin-based performance group, with mostly Russian artists, did a spectacular show with fireworks, dancing apples, a naked horn blower, dumping an accordion in a drain hole, orange smoke and a black flag waving while paper snowflakes fell down on the public.

- Anastasia also organised a trip to a former Soviet building, parts of which possibly will be converted to SPAR residency studios. The relics from Soviet times – murals with heroic factory workers, red mosaics, bronze statues of model workers, abandoned trash in creepy cellars and a coat rack with genuine fur hats made the trip a real treasure hunting adventure.

This sunspot is mine: two exhibitions in St. Petersburg

Mels Dees, 25-06-2017

For an artist, the experience of visiting an exhibition will often differ slightly from most other people’s. Seeing someone else’s work may feel as if you enter his/her bedroom. Or his skull. Or, indeed, his studio. If there is any kind of rapport, you, as an artist, will be able to see what the exhibiting artist is trying to accomplish. And sometimes you are able to judge if his or her effort is successful – and that may make you happy, just happy. Or it can make you feel superior (such a lazy solution!), angry or envious.

But to me, the very best exhibitions I saw as an artist always made me think: I want to get out of here. I have to go to my studio straight away and get to work. Because, yes! This is what art is about and I cannot waste another minute to make it clear – in my way. And you dig in, you work and work, until you even forget who or what it was that got you so excited.

However, in St. Petersburg I found out that there are more ways in which other people’s art can support an artist: it may, for instance, make you feel at home. In this city I realized once again that making art is a way of living. Not just a career, not a way to create wealth or fame. It can, and maybe should be first of all, a way to create fragments of meaning, tiny chips of our dark and immeasurable reality that become intimate household objects. This sunspot is mine.

During the past month or so, two exhibitions in St. Petersburg have given me that almost forgotten feeling, the feeling that it’s all right. That it’s all right that all of us are working our ass off to create something worthwhile, while very few people understand or even care. And even that it is all right if you are barking up the wrong tree, selling nothing or getting no audience as long as you or someone else derive a moment of understanding from it – and probably even if nobody ever does.

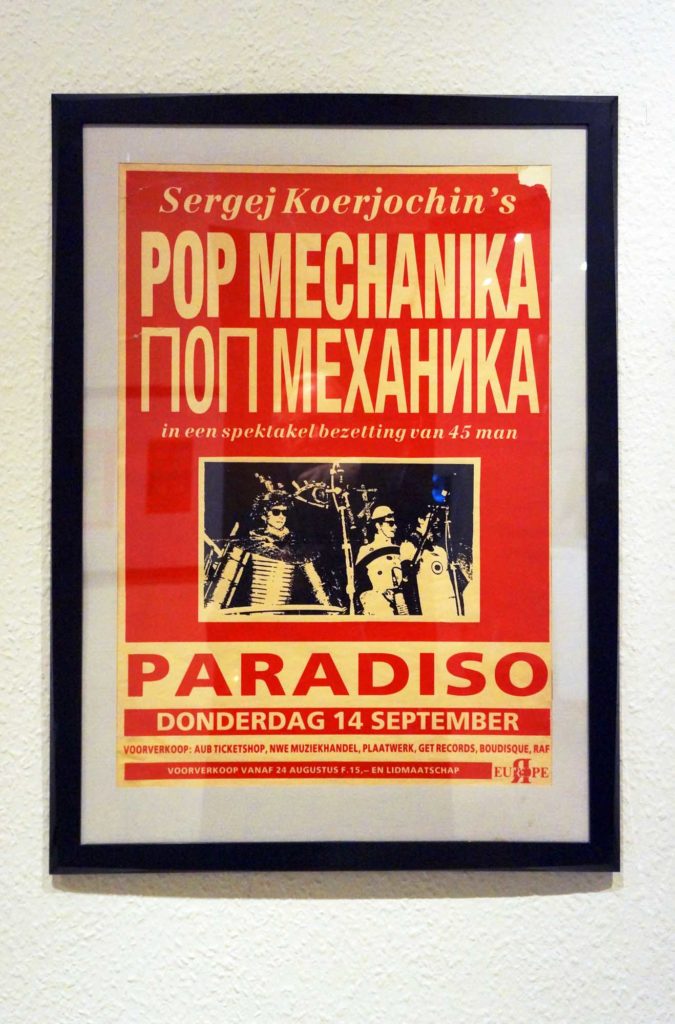

ART MECHANICA at Kuryokhin Center

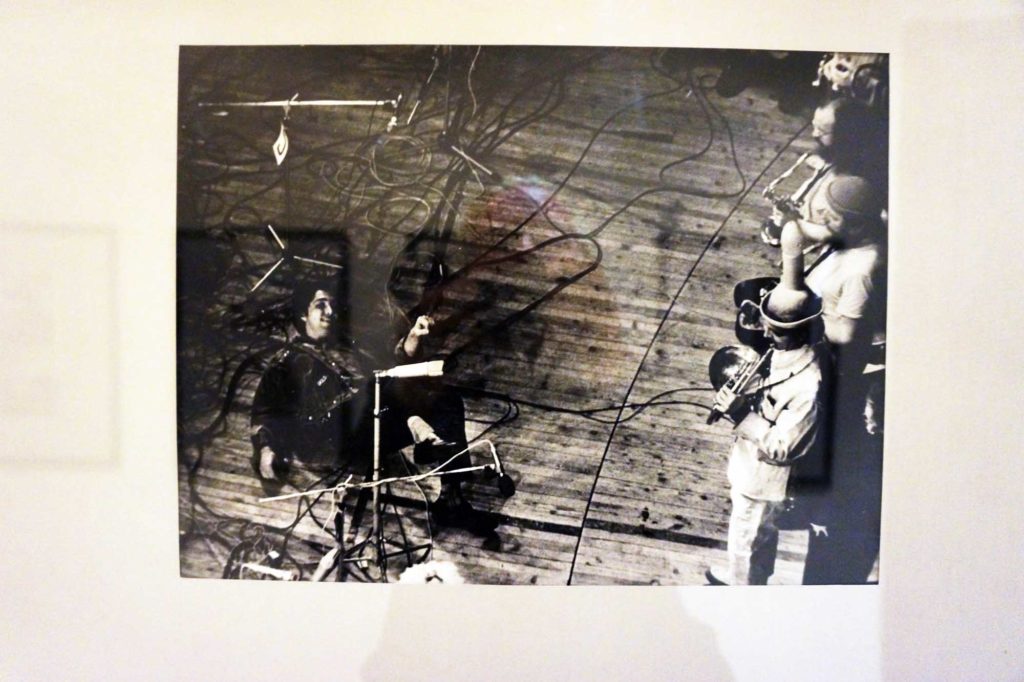

In the nineties, performance artist Sergey Kuryokhin travelled around Europe with his Pop Mekhanika show – and of course visited Amsterdam as well.

His shows were seemingly chaotic but mostly well-choreographed, featuring for instance a military band, choirs and a host of pop and jazz musicians

The first exhibition, Art Mechanica at Kuryokhin Center, often evoked the time that St. Petersburg still was Leningrad and art was a game you played against the establishment, authorities and stuffy teachers. In the ’80s and ’90s, Kuryokhin was a famous composer, pianist, experimental artist, film actor and writer from St. Petersburg. Several recordings of his wild and exhilarating performances were to be seen (to get an idea, see Sergey Kuryokhin live in Helsinki 1995, on YouTube), and the other artists reflected their mood, although in a less violent and restless way.

Ludmila Belova created the installation Overture, with 3D-printed porcelain figurines and music by the 17th century composer Jean-Baptiste Lully. This short movie fragment gives an impression (although the music is mostly drowned out by other sound installations).

The spherites is a complex installation by Daria Pravda, representing the ceremonial room of a fictional sect, the Spherites, which is supposed to have developed in Kronstadt, an island fortress close to St. Petersburg

Visitors can partake of the ceremonies of the sect, dating from the 60s, with typical soviet-era paraphernalia and a mystical spheroscope

.

For his sound sculptures Sergey Filatov uses high-tech materials and advanced technology to obtain subtle, sometimes barely audible effects (see and hear this fragment). He also is an author and musician, and he develops musical instruments.

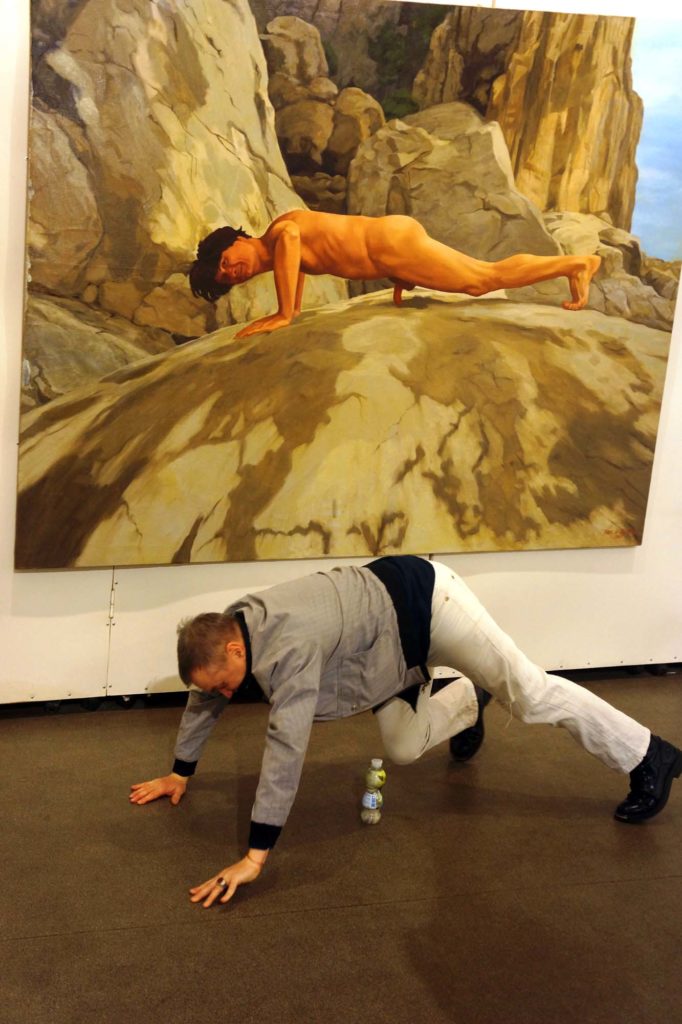

‘rejected’ in the museum for non-conformist art

The second exhibition is in the Pushkinkaya-10 museum in St. Petersburg. Its title, Rejected, suggests connections with the ‘Salon des Refusés’ in 19th-century Paris, or with the Russian underground abstract art in the 1970s. But the exhibition shows that art can be rejected in many ways. There is a painting that was created because a piece of canvas was spread on the floor to catch the paint dripping from the piece Ivan Olasyuk was working on. ‘It received everything the other painting rejected’ – Olasyuk framed it years afterwards.

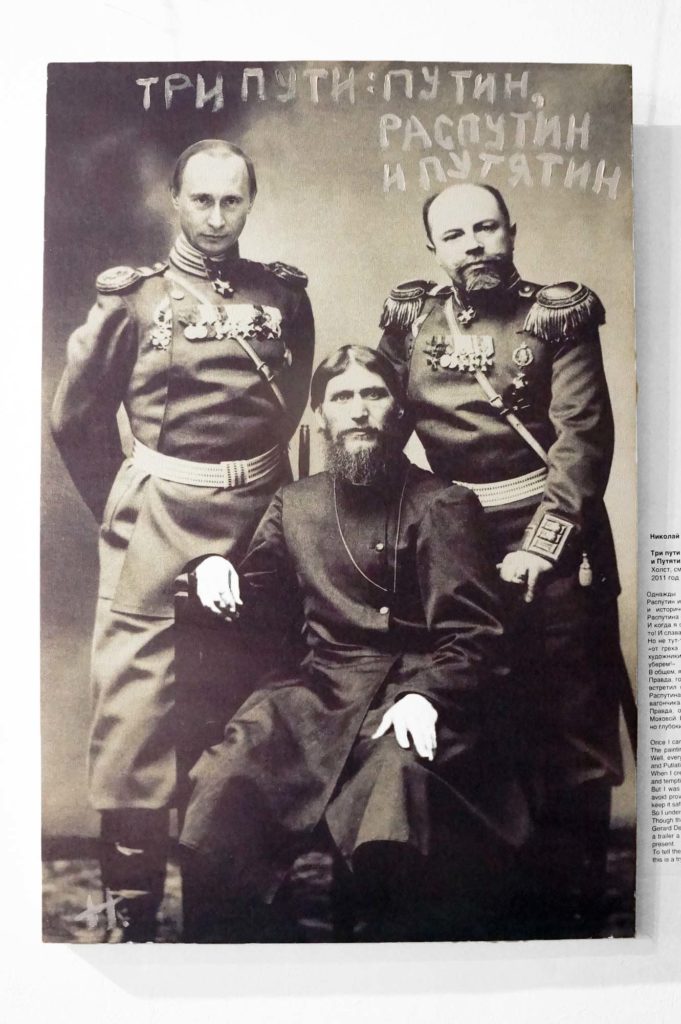

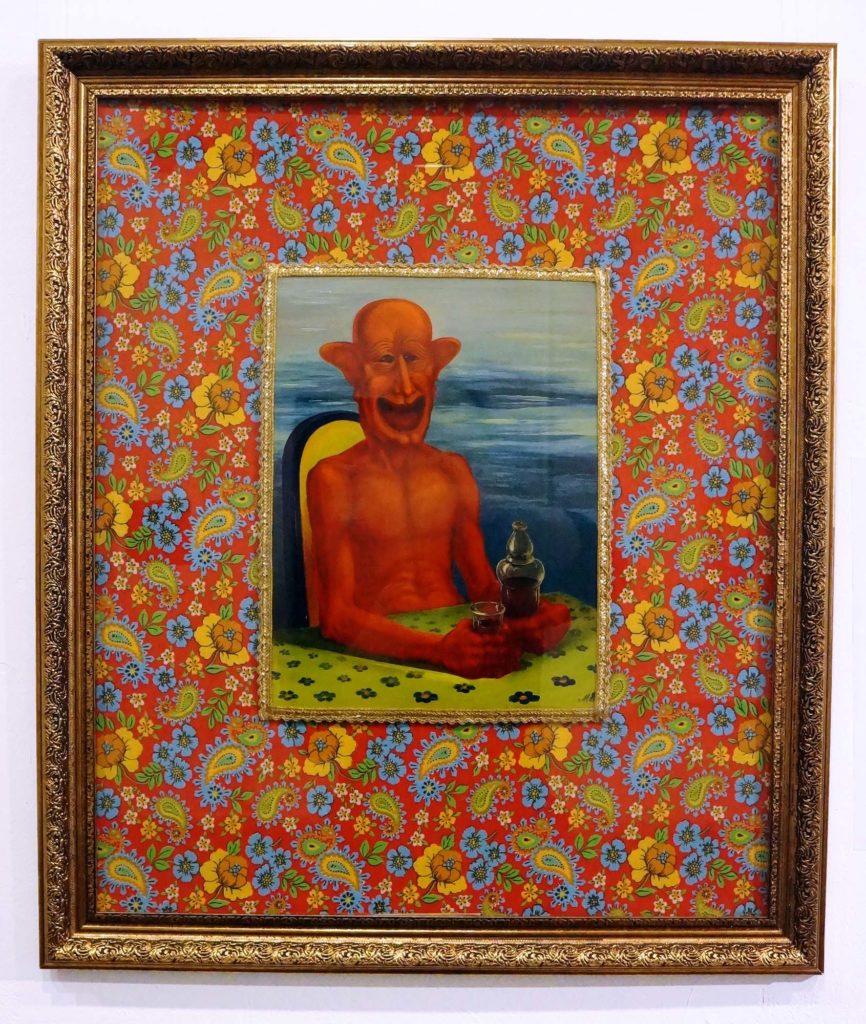

Of course, there were a lot of works that had been rejected in a more literal sense: Nikolay Yakimchuk’s collage of Putin, Rasputin and Putiatin (a 19th-century Russian Admiral) has been refused several times ‘because of the risk it would be damaged’. And ‘Alcoholorous’ by Mikhail Melnikov-Serebryakov was not accepted in the ’80s, because the exhibition committee said: “We all love drinking, and you’re criticizing such an amazing habit!”

There were other obvious reasons why painting had been rejected or somehow ‘got lost’:

The model depicted is a rather well-known Russian art critic, while the artist shows how he constructed the image

Andrey Chezhin’s Soap Opera had not been shown before

Even here the fly-ridden paraphrases of Malevich’s sacrosanct Black Square by Alexander Goncharuk were so controversial that the wall tekst was ripped off

The ‘Rejected’ exhibition was a pleasant surprise, which was not in the first place due to the superior quality of the works (although there was some pretty nice stuff), but because it contained a laid-back and humorous comment on St. Petersburg’s history of censureship and struggle for artistic freedom. Things obviously have not been easy for the artists here, but most seem to cope with a kind of carefree impudence. On top of that, the collection stressed the fact that a lot of the rejecting was done by the artists themselves, on the basis of their own criteria and judgments. And finally, the show as a whole implied a sly poke in the eye of the curators themselves, who are the new ‘powers that be’, the judges on which the artists’ success or failure depends in these neocapitalist days.

PUSKINKAYA ARTISTS

Mariëlle van den Bergh and Mels Dees, 14-06-2017

By now, we have got to know some of the inhabitants of our building, Art Centre Pushkinskaya-10. Let’s start with young Sasha, a sound engineer who helped us with our presentation at the Museum Night, together with his colleague Dimitri. When we returned the beamer to his studio we found him with the cat Marushka. Marushka is a temporary ‘lease’ guest at Pushkinskaya. She has only one eye, a feature dating back to the days of her life as a street cat. She doesn’t know how to purr, but she and Sasha sometimes collaborate in making works of art. She stretches out on the warmest place in the room: the copy-machine, and Sasha presses the button. Sasha also works in the sound studio on the second floor and in his spare time he composes electronic music. Some time ago he played with the idea to go abroad and study electronic music, but decided he was fine where he is right now, doing exactly what he likes. He also collects rare music on a special site on the internet, but he is only interested in rave music from 1980 to 1999. He has a hundreds of followers who attend his concerts, when he acts as a DJ. For people interested in a special, rather nervous variety of electronic music check this out, or if you want to hear Sasha’s own music:http://vk.com/oldrave

Sasha and Marushka

Cat art

The next artist we came to know is Mikhail Kokorin, the maintenance man. After installing our new washing machine he showed us his wood mosaics. It is a typically Russian craft and he is good at it. How high the standard is can be seen in the Hermitage, where a lot of floors are made from precious woods, composed to the most intricate patterns. Michael showed us his kingdom, hidden behind the door with a “Komadante Hulio” sign and adorned with a cannon. During the twenty years he has worked in Pushkinskaya, he accumulated an enormous collection of works by the resident artists. We see his problem: there is more art than wall space. In his homely room in the back there is a series of his intarsia icons, in various kinds of wood, carefully shaped and inlaid.

Mikhail

Mikhail’s intarsia icons

Yulia, curator of the exhibition in the Great Hall introduced us to painter Ivan Olasiuk. We speak German with Ivan, who worked as an artist in Germany for some years after the Soviet Union dissolved. After staying in a small village near Stuttgard, he lived in a house in Berlin that was rented by German friends and where Rolf Biermann was a frequent guest. Ivan had exhibitions in Germany and other countries and we are impressed by his paintings. He says he wants to work in a human world: “Arbeiten mit einer menschlichen Welt”. Slowly his paintings seduce you. Layer upon layer can be unravelled, as on an old painted wall. There is a lot of depth in theses seemingly simple works. Language is very important for Ivan and to him, only the Russian language can express what he intends to say. But then again: Ivan is a visual artist and his true language is visual. Ivan sometimes works on a painting for years, revising it carefully until it is right. Surface is very important and Ivan has developed unique techniques that give the canvasses a worn-down appearance or just the opposite: very velvety and shiny. He doesn’t adhere to a fixed style or school. Sometimes he also inserts objects like photo’s. The painting “Das Kind” (The Child), which has an old picture of his daughter at the centre, encircled by velvet, rather erotic symbols on a deep purple surface. The symbols are his merged initials. We were lucky to encounter a fresh black painting, which he started as an kind of action painting at Museum Night, so the public could witness its evolution.

Ivan’s black painting

More about Ivan Olasiuk, see the short biography written by Yulia Pliashkevich: Ivan Olasiuk

We visited Anatoly Vasilyev in his studio, where he was preparing an exhibition in the Great Hall in Pushskinskaya in November. The title of this show will be “Wise Men” and Anatoly works with silhouettes of popes, Russian Orthodox priests but also with silhouettes of artists friends. Cutting silhouettes is a craft that was popular in the mid-18th century. Anatoly uses silhouettes and combines them with different graphic and painterly techniques to create his own universe.

Yulia took us to a door with three apartment/studios; she herself is staying in the space of Gennady Manzhaev , who is in his home region of Siberia, but we can visit his studio. There are icons and paintings and chairs with hand-sewn textiles parts and then we see more icons, also hand-sewn. These collages are quite special: varying from a Maria with child to Soviet icons with a red star and other political or social symbols. They show great sensitivity and a sense of humour as well, and we fall totally in love with them.

![]()

For pictures of his work go to this link and scroll down to the pictures: aslan gennadi

Nextdoor is Alexander Lotsman, a painter and draftsman pur sang. He works from nature, also plein-air, producing small oil paintings, graphic work and some pastel drawings. Alexander origins lie in the Baikal region (Siberia) and he likes visiting his old stamping grounds to fish and paint outdoors. But he also worked in France and the Crimea. If the weather is too harsh, he will build a simple plastic tent. We see gripping landscapes, beautiful evening light on small wooden houses and snow-covered villages.

The third artist is Aslan Uyanaev, who originally trained as an architect, but became an artist instead. In Art School he had to make figurative drawings and this, as often, developed into abstract painting, which he has been doing for the last 22 years. In his studio we can see quite substantial canvasses, nearly all square. The format turns out to be based on his material: jute canvas from old sacks. The shape suits Aslan well, because he often works on the canvas while it is flat on the floor, so he can easily add elements, only deciding afterwards how it should be hung on the wall. His colours are bright and there is a light atmosphere in his work. Sometimes numbers appear, but they just seem to be a pictorial element, like the vague faces on black-and-white copy paper. Aslan is one of the few artists with his own website: www.artisi.ru and he is, like Ivan Olasiuk and Sergej Kowalski, one of the founders of Pushkinskaya-10.

Aslan’s work

Aslan’s chair

Sergei Kovalsky,another one of the ‘founding fathers’ of Pushkinskaya-10, showed us his studio and immediately initiates us into his philosophy. We see his first painting from 1969 and we are shown the last painting, part of his ongoing project to paint memories inspired by specific music pieces as heard on a specific moment in time. We marvel at an “Alternative Icon”: green, with a hollowed-out centre: “The sacred place is empty”. We see Kovalsky’s version of the vast Parliament painting by IIya Repin in the Hermitage. Here the identical politicians are grey-faced and there are a lot of da’s (yes) in the air. In a corner of his studio we discover a display case with the leftovers of a charred, black piece of wood. Sergei claims to have dug it up from Malevich’ cemetery, during a big public performance. Of course the painting is square. It’s a comforting idea that our Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam still has one black square left….. Another ongoing project is his Parallelosphere Philosophy. On this website, you will find a film by Monica Bernotas about Pushkinskaya-10 and Sergei Kovalsky explaining the history of the art collective and some of his art.

Sergej’s Hollow Icon

On Rachmaninov’s Music

On Lenin

Read this text by Yulia Pliashkevich about Sergej Kovalsky.

Sergei Kovalsky’s website is: http://www.p-10.ru/kovalskij. If you click on pictures&music (left icon) and pictures&music&poesi-2 (right icon), you can download two great films about colours, music, paintings and poetry. See this short fragment to get an impression of Sergej’s multimedia report of the early action days at Pushkinkaya.

The building of Pushkinskaya counts 34 studios, populated by musicians, filmmakers, actors, poets, painters, sculptors and other artists. From these studios around 10 are occupied by female artists. One of them is Xenia (Eugenia Konovalova). She was born and educated in Volgograd. She had many exhibitions, some in foreign countries. In 2006 she founded the DVER gallery/Open Door Gallery at Pushkinskaya-10. In fact we have seen her at work as a curator, explaining art in the corridors to visitors of the Museum Night.

We soon discovered Xenia’s brilliant ideas and sparkling personality. There was a catalogue with pictures of the ongoing project “Carrier Cockroaches project”: big insects from Madagascar, with oldfashioned postage stamps stuck on their backs. Each stamp carries the picture of an artist. Xenia collects artist’s-stamps-on-cockroaches as she collects languages. As in the project “Close Gibraltar, Save Venice” for a future group show. Mels is able to oblige her in several foreign tongues. She will paint the translated sentences on rocks which are (nominally) from Gibraltar and should be used to build a dyke in the Mediterranean Sea to save Venice.

Cockroach art stamp

Another painting with dark mountains turns out to be a nostalgic painting about the spoil tips in the Donbass region, where she spent holidays in her youth. Xenia plays with language as she plays with coloured paper, cutting up and sticking pieces together, using free collage techniques. In her tiny studio we see a big painting of the sunken nuclear submarine Kursk, a round painting of the space ship Mir, another live black cat (two eyes) and a movable “Green house”, a portable Art Gallery on wheels (see YouTube movie), which she takes out on the streets with whatever art she thinks people should take notice of.

Alien with herb family on earth

Museum Night

Mariëlle van den Bergh and Mels Dees, 25-05-2017

A few days ago Museum Night hit Saint Petersburg. A huge event, lasting from 18.00 on May 20 till 6.00 in the morning of the 21th of May. St. Petersburg public transport was running all night to acommodate the thousands of visitors moving from one venue to another. As it said on the internet:

Of course the Museum Night also involved Art Center Pushkinskaya 10, the organisation which hosts SPAR, our residency programme, the Museum of Nonconformists Art, Museum of the New Academy of Fine Arts, Sound Museum, many galleries, the Fish Fabrique music club and studios of artists and musicians. Preparations had been in full swing for weeks with at least half the building being involved in the event itself.

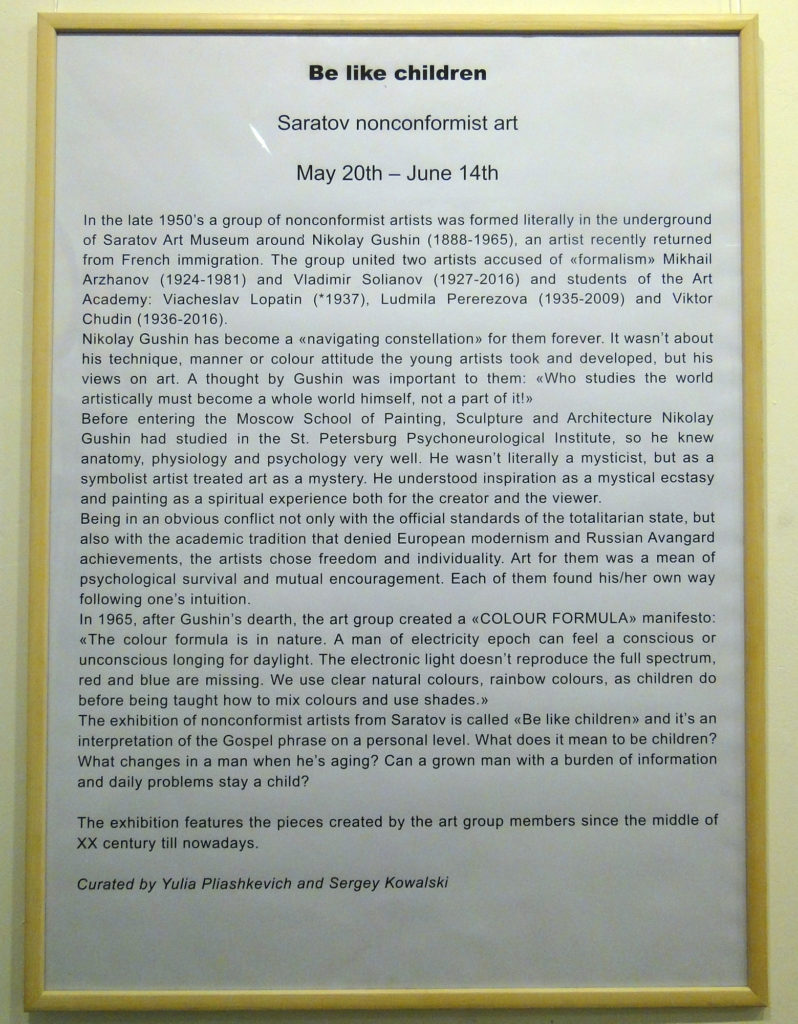

On Saturday afternoon the show Be like Children, Saratov non-conformist art opened in the Museum of Non-Conformist art. It was curated by Yulia Pliashkevich and Sergey Kowalski. This underground group of artists literally worked from the basement of the Saratov Art Museum – Saratov is a city on the Volga river, in the south of Russia. The group’s history could be read on a poster at the exhibition.

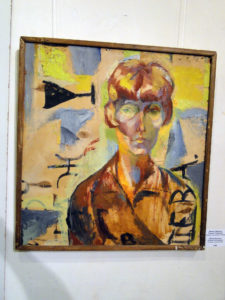

The group consisted of five artists, of whom only one member survives. The exhibition shows works by all artists, both from early times and more recent periods. There is a film featuring Vladimir Solianov, who made abstract work and shows drawings on the Volga shores of bathing people. Many of the exhibited works are executed on cardboard or wood from the museum’s transport crates. You still can see the lettering and the FRAGILE wineglass symbol. Yulia explains that very little material was available in those years. Artists had to improvise with whatever they could get.

Documentatiefilmpje Mels

Documentatiefilmpje Mariëlle

As SPAR artists we were involved in two items during Museum Night. We had an beamer presentation featuring work by both of us, accompanied by our son Quirijn Dees’ music. When selecting the works for the show, we kept Ecology, the Museum Night’s central theme, in our minds. We also showed our film Water (2004), made in collaboration with the late ballet dancer Lén Staals.

Our other activity was to conduct a workshop using waste materials – cardboard, plastic, cans and more – to recycle them into art works. Mariëlle made a mobile from beer cans and a wire clothes hanger as an example and to inspire people. It started off a nice collection of tin mobiles.

The hit of the night were the ‘monsters’ made from small waste objects Mels had injected with Styrofoam. If people got inspired and their fantasy was triggered by the weird shapes, they created the craziest beings on stick legs or sprouting from beer cans. In a couple of hours three big bags of foam objects were processed. Some of the resulting works were taken home – but many were lined up in a parade on the podium wall.

Samizdat History

Mels Dees 18-05-2017

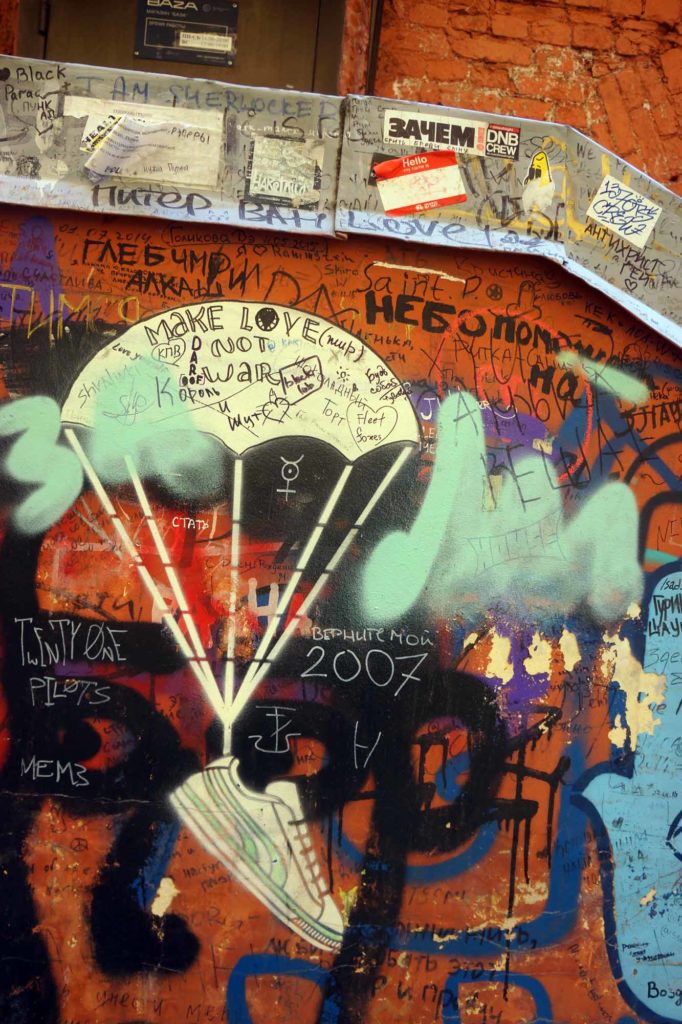

Soon after arriving at SPAR, we started to realise we were living in a monument of sorts, or at least a tourist attraction. The complicated entrance (we have to go through a porch off Ligovsky Prospect, then a door, past the doorkeeper, down a stairs, out by another door, cross a small courtyard full of graffiti, pass a second porch to yet another courtyard, open a door with a primitive electronic lock, go up two flights of worn-down marble stairs – the lift isn’t very reliable – and open our apartment door with an aged brass key), this complicated entrance then, is often full of admiring Russian people taking photographs and selfies against the background of aging posters and improvised artworks.

The artwork at our front door. At unpredictable times it comes alive and clangs about a bit

The visitors range from very young and hip to old and pretty haggard and sometimes seem to be on a kind of pilgrimage to this place, which has been a stronghold of Soviet and Russian subculture since the ’70s. In one of the corridors there is a permanent exhibition about the political Samizdat during the ’80s, while there are several other, sometimes rather obscure exhibitions spread through the buildings, such as The Museum of Sound and The Rock Museum.

The Rock museum – consisting of only two small rooms – captures the spirit of freedom and resistance rock music used to spread during Soviet times and beyond. Obviously, it is inspired by the ’60s western pop culture but it has both a more existential and a rather home-grown look. Hardly surprising, as records and magazines were not available and song texts had to be copied in writing or with typewriters. Even electric guitars were almost impossible to get, and the museum shows some examples of beautiful home-made models.

The initiator of the rock (POK) museum is Vladimir Rekchan. He is an enthusiastic collector and one of the few old Leningrad Rockers still living to tell their stories of the seventies and before. Many of his friends have succumbed to age, drugs and rock and roll. Or to wodka, like Rekchan’s artist friend Sergej Lemechov. His underground drawings are toxic jewels, incredibly detailed depictions of the private and public hell he lived in. In the west he is virtually unknown – his work deserves more than that.

Victory Day

Mariëlle van den Bergh – 15-05-2017

We were lucky to witness the 9th of May celebration of the victory that ended the Second World War in 1945. In Russia you sometimes get the impression this victory was entirely accomplished by the Russians alone. Anyway, it is an event that evokes the ‘great’ Soviet area, so you see the hammer and sickle and the red flags reappearing everywhere. The main street in Saint Petersburg, the Nevsky Prospect, is decorated with stylish banners, flanking golden stars, all in a rather cardboard fashion and hanging high above the streets. On the sidewalks the commercial advertising pillars now show pictures of some of the fallen heroes. They are printed on huge posters, with their full names and other details on display. They were all different – it was impossible to find doubles. So each poster seemed to be a unique print, made only for this occasion. There must have been thousands of St. Petersburg’s fallen sons on the streets on the 9th.

The day started with parades everywhere but the main one was in Moscow. Here in St. Petersburg we had been able to witness the construction of the stand for the parade on the big square in front of the Hermitage, when we queued to get in the museum a few days before. The parade started simultaneously all over the vast country at 10.00 A.M. Moscow time. We were able to see it on a live television broadcast. Russian president Putin was of course overseeing the whole ceremony, which lasted for hours. Later we saw a compilation of the festivities in other regions. What they all had in common were the vast electronic displays in the middle of squares, showing the Moscow celebrations in real time.

Anastasia, the director of our residency programme SPAR, filled us in on some background information about the March of the Immortal Regiment. In the afternoon of the 9th of May, family members march through the streets, holding placards with pictures of beloved family members that died in WWII. Usually they also wear a bow of a orange-black ribbon on their breast. Sometimes they wave red or Russian flags. Mels and I went to see the fireworks at night. Coming and going over the Nevsky prospect, we submerged in the lively and cheerful crowd. There were families and bunches of youngsters afoot as were couples of all ages. Every hundred meters you would encounter a new treat like a living statue, a vendor of balloons, pigeons, a dressed-up bear, a beautiful girl in Louis XIV style, and so on. You make a selfie with them for some small change. And of course musicians would play. The merry fans would wave banners or MacDonald flags and sing along the popular Russian hits. We listened to two aged musicians, one playing the accordion and the other singing in a well-trained opera voice. Someone would toss them a banknote and ask for a special tune and then the whole small group sang some alltime favourite with dedication and ardent patriotism. Look at the video below!

At 22.00 the fireworks started. The great booming sounds of cannons were heard everywhere and quite a crowd had gathered near a canal, from where you had an unobstructed view over the bridges and boats. The intriguing en quite complicated firework show lasted only 15 minutes, but was served in a continuous programme of beautiful pictures. The crowd cheered each time to show its appreciation. When it was over, no time was wasted and the St. Petersburg mob hurried home at full trot, or to a restaurant or railway station.

CROSSING BORDERS

Mels Dees, St. Petersburg 03-05-2017

Instead of slowly travelling by boat and car for many days and thousands of kilometers – as we did on our way to the Reykjavik residency – it took us just a few hours to get to St Petersburg. I know, it has become commonplace to virtually everybody, but I find air travel increasingly humdrum and shallow. Both your origin and your destination are depersonalised, dissolved in a heavy mist of commercial imitation luxury. And during the first days at your destination everything remains slightly unreal. The soul travels by horse, indeed.

But when I look at the pictures I took over the past few days, the contrast becomes clear. Compare the idyllic picture of the wooden Foot I installed for the manifestation KunstenLandschap at Enschede, the Netherlands, with the violent (although humorous) art at entrance of our St. Petersburg residency.

The good thing was that, on the very first day, we lost our way in the outskirts of Piter. Nothing like getting lost in an unknown city to convince yourself of the reality surrounding you. However, behind the former Iron Curtain, few things are what they appear to be. The past tends to bend everything out of perspective and provides wry interpretations of even the simplest things.

Walking along Lygovsky Prospekt, just outside St. Petersburg centre, we passed a seemingly endless, yellow-painted wall. It looked like a 19th-century park wall, with the trees and the manor inside burnt down in revolutionary times and replaced by ugly industrial sheds.

However, on investigating the structure, it turned out that the wall had been extensively repaired – or even built from scratch – using Expanded Polystyrene (EPS), which must have become available in the Soviet Union only by the 70s or later.

So what happened on Lygovsky Prospekt? Was it an attempt to hide the ugly buildings from tourists behind a fake facade, comparable to the Potemkin Village built for Catharina the great? What about the other buildings in town? How real are they?

CONTRASTS

Mariëlle van den Bergh, St. Petersburg 04-05-2017

There couldn’t be a larger contrast between being an artists in residence in Iceland and being one in Russia. Yet, with only a three-weeks touchdown in Holland, Mels and I switched from one to the other. We took the airplane at Schiphol, Amsterdam and arrived on the first of May in Saint Petersburg.

Let’s compare. Iceland is Europe and Russia isn’t. To stay in Iceland there was nothing to arrange, just go there. To stay in Russia, you have to apply for a visa, and be officially invited by a Russian art organisation. In our case that was SPAR, Saint Petersburg Art Residency. www.artresidency.ru

Also, although Saint Petersburg is only two hours and 20 minutes by airplane from Amsterdam and much nearer than many destinations in Europe, it is not considered to be European. You need to check your health insurance polis for instance, if you are covered for this part of the world. Saint Petersburg is the second largest city of Russia and competes with Moscow for being the nicest, most urban, sophisticated, wealthiest, etc. city of Russia. It hosts a couple of million citizens while Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland, has little more than 100.000, one third of the country’s entire population. So Saint Petersburg is a big city. While in Iceland, we stayed at Korpulfsstadir, ten kilometers outside the centre of Reykjavik. In Saint Petersburg, we are right in the heart of the metropolis. As an illustration I include the views from both our apartments.

Both countries have their own currency, but there’s a huge difference in what you can buy for it. For instance: the price of a beer. In Iceland it is hard to find one in the first place. In special liquor stores, the Vinbudin, a nice home-brew beer would set you back some € 8. Which is the same price at Happy Hour for a pint in the local Reykjavik pub. Mind you – during Happy Hour you only pay half the usual price of the drinks. In Russia every supermarket has a broad range of alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks. Especially the Vodkas are omnipresent, but one can also choose from a real good variety of local and international beers and wines. A Russian pint can of beer is to be purchased for €1. We haven’t been in pubs yet, but you get the idea. There is a lot of food available in Russia and it has its own specialities, like a broad range of mayonnaise (with mushrooms, with herbs, with meat, with this or that fish), ditto pickled vegetables, and local pastries.

The other difference that catches the eye is the population on the streets of both capitals. While the general population of Iceland descends from Vikings and the rest of the people in Reykjavik consists of tourists, mainly Asian, in Saint Petersburg you will mostly just see Russian citizens.

But what a tremendous country it is! Its population ranges from Caucasian to Mongolian to Persian types. Although almost everybody speaks Russian and is Russian, it provides a very international atmosphere. Crossing the Russian border and continuing to travel through the same country, you could cross Europe several times over before you reach the end of Russia. I like this feeling a lot even if, in the tiny country that Holland is, you can also meet many nationalities. And sometimes visitors from abroad are already freaked out by the fact that we are with over 17 million people.

Go West…

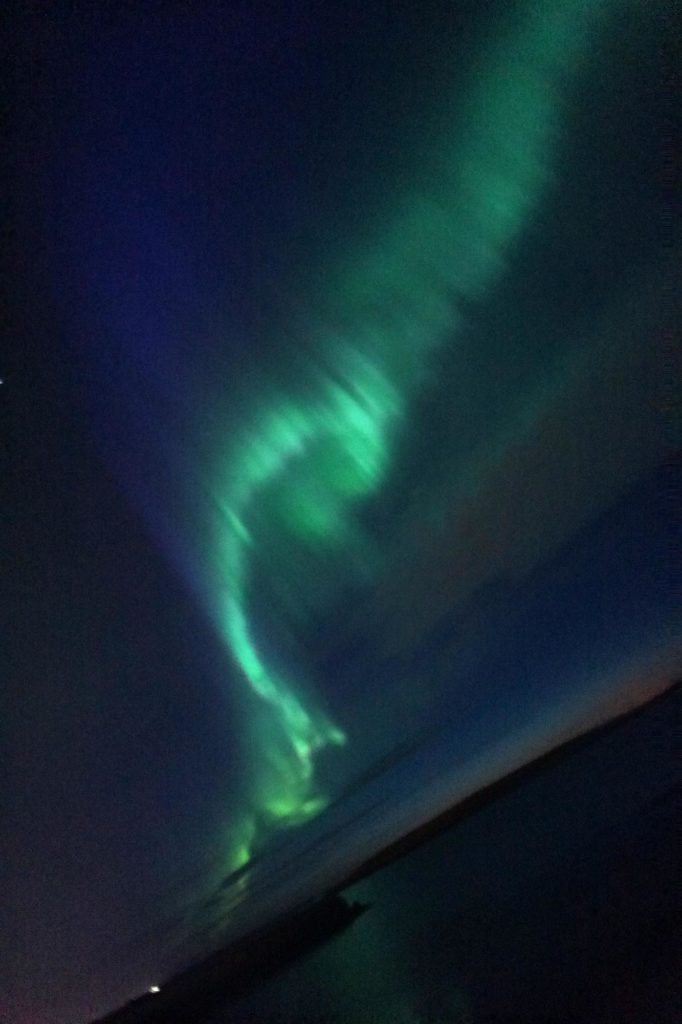

Mels Dees, Reykjahnid 04-04-2017

Let’s start with the northern lights, just to get them out of the way. In the first place, the famous colours are not there to be seen with the naked eye – they are quite real, but only turn up clearly on photographic images. So most of the time, you can’t even see what it is you are taking pictures of. And then, afterwards on the computer screen, the aurora shapes and colours are literally stunning: there’s not much more you can say about them but ‘Aaahh… ‘.

After missing out on a few occasions (a concert, a dance performance, or plain forgetfulness) we managed to see the lights in full splendour while we were outside. In spite of their variety in shape and form, the northern lights tend to appear monotonous to me – after a while I experience a kind of excited boredom. And you can get amazingly cold while watching.

But ok, here’s some more:

At this moment it is very hard for me to think of employing Aurora Borealis for any convincing artistic purposes. I mean: what can you do with it? I don’t know yet, but who knows, that day may come.

In the mean time, we had our work cut out trying to interpret Iceland’s wild, harsh and largely incomprehensible nature . Our one-month residency at SIM in Reykjavik allowed us to travel around and explore just a tiny part of the country. Even though our expectations were high, we kept being amazed at what we saw. It was hard to make any speed while travelling – there was simply too much to see. By painting, photographing and making collages, we tried to make some sense of it all.

How to get there?

Mariëlle van den Bergh, 04-04-2017 Reykjahnid

Then there is the subject of travelling to and in Iceland. It is very fast and convenient to take an airplane to Keflavik, the airport 50 km. west of Reykjavik and then the shuttle to town. Which we didn’t do. We took our old Volvo, drove it 1000 km from Eindhoven in the south of Holland to Hirtshals in North Denmark and boarded the Smyril Line Ferry. This trip takes three days and nights including a stop in Tórshavn in the Faroer Islands. In the picture we were passing the Orkney Islands.

Since we started out at the end of February, there was a good chance we would run into a storm at sea as well. As in fact we did, which meant that the captain ran the vessel faster than scheduled and skipped most of our stay at the Faroer. We sailed ahead of the storm and reached Seyðisfjörður in Iceland half a day early. Seyðisfjörður is a lovely small fishing town at the end of a fjord on the east coast of Iceland. It is also home to the artist residency, café and exhibition place Skaftfell, which was founded by German artist Dieter Roth.

We had rented a beautiful wooden cabin, overlooking the fjord and 3 kilometres outside of Seyðisfjörður, a bit up the mountain. Since a fresh pack of snow had fallen, we learned our first lesson about Iceland: the weather is not what you thought it would be a day ago and it can change very quickly. In fact we got stuck on the way to the accommodation and had to put on the snow-chains. We were saved by the host of the cabin. Icelanders are able to drive during winter using tyres equipped with spikes. We came to get used to the strange sound of spiked tyres in the streets. A very useful website is the www.road.is. This reports on road conditions very accurately and is updated continuously. The weather is harder to predict (www.vedur.is). Only the most recent news proves to be accurate. But this is Iceland: the next day it can be totally different: sunny or grey and foggy or a snow storm. The main road around Iceland is the 1. It goes around the island, following the coast in the south and cutting through mountains in the north. Doing this, you will encounter the most breathtaking scenery.

Teeming cultural life

Mels Dees, Faroe Islands, 06-04-2017

Icelanders – how do they do it? As soon as you start getting some idea of the size of the country (more than twice the Netherlands), the tremendous natural obstacles to infrastructure, agriculture or any other type of human civilization, while realizing that it has fewer inhabitants than The Hague, you start wondering how they got the place in its present well-groomed state. Granted – energy in Iceland is virtually free and green, there are quite a lot of foreign workers (mostly Eastern European), and Icelanders themselves work almost day and night (mostly because life is so expensive).

But to me it remains an enigma.

The same goes for cultural life. It is incredible lively and many-coloured, not just in Reykjavik, where more than half the population lives, but also in the country. Reykjavik boasts one of the world’s most beautiful and intriguing Opera Houses (Harpa, built in collaboration with the artist Olafur Eliason), but there is a plethora of artists’ initiatives, small theatres, museums, exhibition places and it looks as if, as soon as a building is abandoned or being reconstructed, it is turned into a temporary art centre or pop-up gallery. And in the sparsely inhabited countryside, in the tiniest fishing villages, you will find any number of artists’ residencies, often well-equipped and up to date.

Also the level is high: almost all professional artists from Iceland are trained abroad and people like Sigurdur Gudmundsson, Hildur Gudnadottir and Jon Arnason are well-known all over the world. Even work from amateur weaving clubs or by semiprofessional painters often looks incredibly tasteful and well-made. But the most impressive is the way artists use every opportunity to develop and show their work – both official and improvised – and the number of people paying attention or involved in the results. During the short period we were in Iceland, we saw numerous exhibitions, some of them so crowded you could hardly get in.

The showpiece of Icelandic culture is the Harpa Opera – doubling as a public square – with walls mimicking the basalt columns Iceland is made of, and built in a stunning setting.

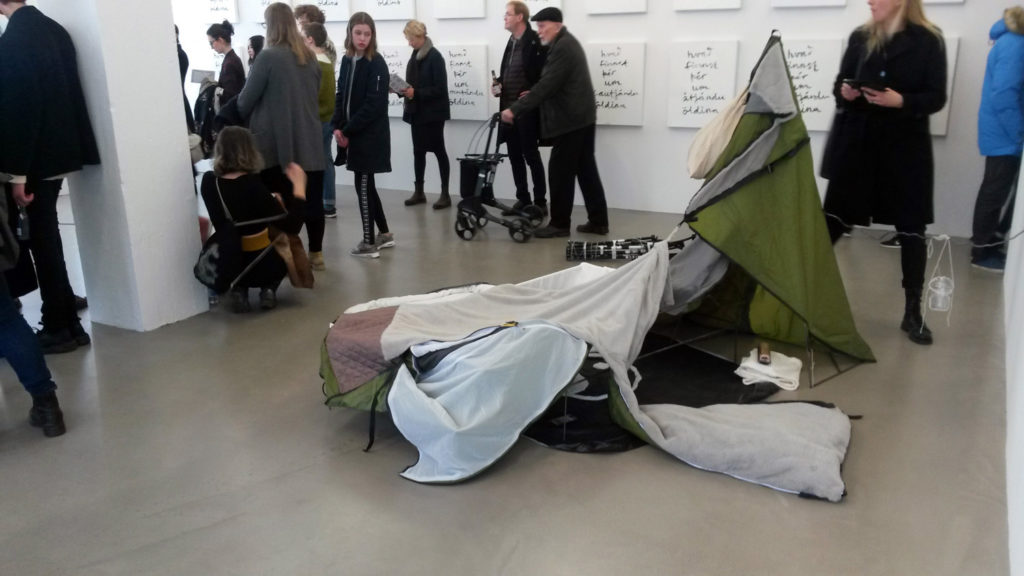

One day we ran into the busy opening of a ‘pop up exhibition’ taking place in a shop being redeveloped in the centre of Reykjavik. The theme of the work was ‘natural materials’, the presentation slick and digital, the public young and decidedly hip.

On another evening we went to a combined art film/dance performance (Fórn (Offer) by the famous American artist Matthew Barney and an Icelandic dance group) in a theatre just outside Reykjavik. Both the dance performance and the film were outrageous. During the interval, a weird cross-dressed Viking held an unintelligible monologue while throwing a clay mug.

DCIM100MEDIAYUN00151.jpg

In the tiny village of Hjalteyri, near Akureyri (North Iceland), a former fish factory run by Gustav Geir Bollason serves as a gigantic studio and exhibition space for visual artists – at least during summer. In winter, the area is often isolated by snow and wind.

Being an Artist-in-Residence at SIM

Mariëlle van den Bergh, Faroe Islands 07-04-2017

SIM is the Icelandic Artists Organisation. It is based in Reykjavik, its headquarters in the town centre. In the same building also houses the gallery. There are three more locations. One is in Reykjavik city itself, on Seljavegur street and a ten minutes’ walk from the gallery. At Seljavegur comprises 10 studio’s for artists in residence, while the other spaces are used as studios or for other artistic purposes. The second location is at Korpulfsstadir, which is 10 km. from Reykjavik. Korpulfsstadir is an old, monumental dairy farm. Besides the 3 rooms for artists in residence, a cosy and spacious kitchen and roomy studios upstairs, it also harbours an (independent) gallery and many small studios for local artists.

The third location is in Berlin and is meant only for Icelandic artists. You can find information on the website www.sim.is Applications are taken twice a year. The residency is one to three full months. During the residency the artist is allowed to have visitors. Our residency was during the month of March at Korpulfsstadir and our fellow artists there were Danish textile designer Gitte-Annette Knudsen and Australian photographer Janet Tavener. Janet was accompanied by husband and graphic artist Rew Hanks. In the other SIM location there were artists from Finland, Italy, Germany, the USA, Thailand, Ireland and Australia and they covered visual arts disciplines like painting, video, photography and sound.

At the beginning of the month SIM project manager Birta Ros Brynjolfsdottir organizes meetings, where artists meet each other, present their plans and show their works in a power point presentation. Birta provides addresses of artist’s material dealers, second hand places, car rentals and whatever else you might need. She also sends mails on events you should not miss, in our case things like the opening of the new Marshall building.

This turned out to be a really important event in the Icelandic art world and indeed the entire local scene turned up. In fact we, as Dutch artists, haven’t seen such a crowded opening for ages and where very impressed. The Marshall building hosts the Living Art Museum and Ólafur Eliasson ’s studio on the top floor. Some of his work was on show. In the seventies, he studied at Ateliers ’63 in Haarlem. Another floor of the Marshall House is taken by the artists’ initiative Kling and Bang.

The art made during the SIM residency is presented at the end of each month. This exhibition will always be a group show. In our case the work of no less than fourteen artists was on show. In between these presentations there are other exhibitions in the gallery, presenting SIM members or visiting artists. Reykjavik art live is very much alive and there is much to be seen.

Icelandic art and artists

Mariëlle van den Bergh, 05-05-2017

In the eighties I attended the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht. In the two years I spent there, I met seven Icelandic artists. Sadly enough out of these seven persons, three had already passed away: Ingileif Thorlacius, Thorvaldur Thorsteinsson and Georg Guðni Hauksson. Thanks to the ‘A3tjes’, the leaflets the students were allowed to publish each year at the JVE, I could Google their names and using translation programmes I could find information and contact the other artists. So in Reykjavik we met with Svanborg Matthiasdóttir and she is a very active artist, an art teacher and organiser of exhibitions, for instance with artists’ books. One of the A3tjes of Svanborg had paintings with horses. Nowadays she and her husband have 30 Iceland horses and she still paints them. In her beautiful home, designed by herself, the Icelandic horses run among the walls and clearly enjoy their freedom. (ARKIR-Svanborg M\myndystaskoli.is/svanborg m\Hotel Ranga-room 36\artist’s Book Exhibition in Iceland/Svanborg Mattiasdottir)

The next artist we met was Helgi Thorgils Fridjónsson, who had been on a residency at the European Ceramic Workcentre with Mels in the past. Helgi is an internationally-known painter. He had recently moved from his old studio to a brand-new one and hundreds of paintings were still lining up to get sorted and stored away. But he was already painting new ones and had them on a wall, standing on adjustable pegs. Among the paintings were the ceramic works and now and then Helgi rather enjoys the change and get his fingers into the clay. (wikipedia\ helgif.is\ icelandicartcentre.is/people/artists/helgi.thorgils.fridjonsson)